Written by: Andy Greenberg, Wired Magazine

Translated by: Luffy, Foresight News

Editor’s Note: Deep in the jungles of the Golden Triangle, the steel structures of scam parks have become a hell on earth for countless people, breeding a series of multinational cryptocurrency pig-butchering scams. Red Bull, a computer engineer from the India-Pakistan border, fell into the trap while seeking overseas employment, but after seeing the darkness, he chose to become a whistleblower. He risked his life to collect evidence in the tiger's den and collaborated with Wired Magazine journalist Andy Greenberg from afar, attempting to tear the veil off this black industry. After Red Bull escaped the den of evil, Andy Greenberg wrote a lengthy article detailing his story with Red Bull. Below is the English translation of the original Chinese text:

A Cry for Help from the Golden Triangle

It was a beautiful night in June in New York when I received the first email from this informant, who asked me to call him Red Bull. At that time, he was in a hell on earth 8,000 miles away.

After a summer rain, a rainbow hung over the Brooklyn neighborhood, and my two children were playing in the children's pool on the roof of our apartment building. The sun was setting, and I was immersed in various apps on my phone, in a typical 21st-century parental way.

The email had no subject line and was sent from the encrypted email service Proton Mail. I opened the email.

"Hello, I am currently working inside a large cryptocurrency pig-butchering scam gang in the Golden Triangle," the email began, "I am a computer engineer who was forced to sign a contract to work here."

"I have collected core evidence of this scam process, with every step documented," the email continued, "I am still inside the park, so I cannot risk exposing my true identity. But I hope to help take down this den."

I only vaguely knew that the Golden Triangle was a lawless jungle area in Southeast Asia. But as a journalist who has reported on cryptocurrency crime for 15 years, I was well aware that this cryptocurrency scam, known today as "pig-butchering"—where scammers use romance and high-yield investments as bait to trick victims into handing over their life savings—has become the most profitable form of cybercrime globally, with annual amounts involved reaching hundreds of billions of dollars.

Today, this intricate scam industry operates in various scam parks in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, sustained by hundreds of thousands of victims forced into labor. These victims are trafficked from the poorest regions of Asia and Africa, forced to serve criminal groups. The result is a self-perpetuating, ever-expanding global funnel of funds that traps people on both sides in a dire situation: one side is the financially ruined scam victims, and the other is the enslaved park workers.

I had read countless tragic reports about scam parks: laborers suffering beatings, electric shocks, starvation, and even being killed by their captors. Most of these stories came from a few survivors who had successfully escaped or been rescued by law enforcement. But I had never encountered someone still inside a scam park who actively stepped forward as a whistleblower—a true insider informant.

I still couldn't be sure if this self-proclaimed informant was real. But I replied to the email, asking him to switch from email to the encrypted messaging app Signal and to enable the self-destruct feature for messages to better conceal his whereabouts.

The informant quickly replied, asking me to wait two hours before contacting him again.

Red Bull Trapped in the Park

That night, after the kids fell asleep, my phone began to receive constant notifications from Signal. First, he sent me meticulously organized documents: a flowchart, followed by a written guide detailing the complete scam process of the scam park in northern Laos. (I later learned that the term "Golden Triangle," once used by Americans to refer to a massive opium and heroin-producing area, now mainly refers to an "economic zone" in Laos bordering Myanmar and Thailand, which is largely controlled by Chinese business interests.) These two documents detailed every work step in the park: creating fake Facebook and Instagram accounts; hiring models and using AI deepfake tools to create realistic romantic partner illusions; tricking victims into "investing" on their recommended fake trading platforms. The materials even mentioned a small gong in the office that would be struck to celebrate whenever someone successfully scammed a victim.

Before I could thoroughly review these detailed contents, I had planned to enjoy a nice Saturday night with my wife, but just after midnight, my phone rang.

I answered the Signal voice call, and a polite Indian-accented voice came through: "Hello."

"What should I call you?" I asked.

"Brother, you can call me whatever you want, it doesn't matter," the voice replied with a shy smile.

I insisted on a name, even if it was something he made up on the spot.

"You can call me Red Bull," he said. Months later, he told me that when we spoke, he was looking at an empty can of Red Bull energy drink.

Red Bull said he had previously contacted law enforcement agencies in the U.S. and India, as well as Interpol, and had left messages with several media tip lines, but only I had responded. He asked me to tell him more about myself, but as soon as I mentioned my work reporting on cryptocurrency crime, he interrupted me.

"Then you are the person I can trust with everything," he said eagerly, "You will help me expose all of this, right?"

I was caught off guard and told him he needed to tell me who he was first.

In the next few minutes, Red Bull cautiously answered my questions. He did not reveal his real name, only saying he was from India, and that most of the forced laborers in the park were from India, Pakistan, or Ethiopia.

He said he was in his early twenties and held a degree in computer engineering. Like most of his colleagues, Red Bull was lured by a fake job offer, which promised him a position as an IT manager at an office in Laos. Upon arrival, his passport was confiscated. He was forced to live in a dormitory with five other men, working on a night shift schedule, with shifts lasting 15 hours, which coincided with the daytime hours of their scam targets—Indian-American victims. (I later learned that this model of connecting scammers with victims of the same ethnicity is quite common, aimed at building trust and avoiding language barriers.)

Red Bull's situation was not as extreme as the modern slavery I had previously seen; rather, it resembled an absurd imitation of a corporate sales department. In theory, the park would incentivize employees with commissions, creating the illusion that "hard work leads to wealth." But in reality, employees were perpetually in debt and effectively enslaved. Red Bull told me that his base monthly salary was 3,500 yuan, about $500, but this money was almost entirely deducted by various illegal fines, the most common reason being failure to meet initial communication targets with victims. In the end, he had almost no actual income and could barely survive on the food from the cafeteria, which mostly consisted of rice and vegetables that he said had a strange chemical taste.

He was bound by a one-year contract, originally thinking he would be allowed to leave once it expired. He told me that so far, he had never successfully scammed anyone, only barely meeting the minimum required number of fake communications. This meant that unless he escaped, completed the contract period, or paid thousands of dollars to buy his freedom—money he did not have—he would remain a prisoner there forever.

Red Bull said he had heard of people being beaten, electrocuted for breaking rules, and there was a female employee he believed had been trafficked as a sex slave, while some colleagues had mysteriously disappeared. "If they knew I was contacting you, that I was going against them, they would kill me directly," he said, "But I swear to myself, no matter whether I survive or not, I will stop this scam."

Collecting Evidence in the Tiger's Den

Then, Red Bull spoke about the urgent purpose of this call: he had learned that the park was executing a scam targeting an Indian-American man, who had previously been scammed at least once but was still being deceived by one of Red Bull's colleagues. The victim's cryptocurrency wallet service provider seemed to have suspected he was being scammed and had frozen his account. Therefore, the park planned to send a contact to collect the six-figure cash that the victim was preparing to pay.

The withdrawal would take place in three or four days, and this victim lived only a few hours away from me. Red Bull explained that as long as I acted quickly, I could notify law enforcement and help set a trap to catch that contact. Besides this lead, he also hoped I could help him contact an FBI agent to serve as his subsequent liaison, while he would continue to cooperate with me as an informant. Our call lasted only about 10 minutes.

Red Bull impatiently said he would send detailed information on Signal and then hung up. A few seconds later, he sent me screenshots of internal chat records from the park, conversations between colleagues and the victim, and more details about the trap he hoped I would arrange.

My mind was in a whirl, and after a brief pause, I unexpectedly called Red Bull back on Signal and turned on the video. I wanted to see who I was talking to.

This is the image captured during Red Bull's first call with Wired Magazine, taken from a Signal video call in a hotel room.

Red Bull answered the video call. He was slender, handsome, with slightly curly hair and a neatly trimmed beard. He gave me a slight smile, seemingly unconcerned about revealing his face. I asked him to show me his surroundings, and he turned the camera to reveal an empty hotel room. He explained that to find a place to talk to me, he had risked renting a room in a hotel next to the office, and outside the window were ugly concrete buildings, a parking lot, a construction site, and a few palm trees.

At my request, he stepped outside to show me the Chinese sign at the entrance of the building. I didn't know much about the Golden Triangle, but everything in front of me clearly indicated that this was it.

Finally, Red Bull showed me his work ID, which had the Chinese name given to him by the park: Ma Chao. He explained that all employees in the office did not know each other's real names.

I began to believe that what Red Bull was saying was true: he was indeed a real whistleblower inside the Laos scam park. I told him I would consider all his requests but hoped to work with him patiently and cautiously to minimize his risks.

"I trust you, I will follow your arrangements," he replied at 1:33 AM, "I wish you well tonight."

At 4 AM, I was still lying in bed wide awake, repeatedly pondering how to deal with this eager new informant, who seemed determined to entrust his life to me.

After a few hours of sleep, I texted Erin West, a prosecutor in California, or rather, as I learned during our call later that day, a former prosecutor. At the end of 2024, feeling extremely disappointed with the U.S. government's inaction against the rampant pig-butchering scams, she retired early from her position as a deputy district attorney and now runs her own anti-fraud organization, Operation Shamrock.

I consulted West on who to contact in law enforcement to assist in arranging the sting operation proposed by Red Bull. To my surprise, West expressed far more enthusiasm for the article Red Bull hoped I would write than I had anticipated. "This is a huge deal," West said, "Finally, an insider is willing to step forward and share this information, exposing the entire scam operation."

However, she quickly dismissed the idea of a sting. She said there simply wasn't enough time to arrange it, and she believed that arresting a low-level contact would not be a significant victory in Red Bull's eyes. She indicated that these contacts were mostly freelancers, lower in the hierarchy than Red Bull, and had no valuable information.

More importantly, whether through a sting operation or my own efforts to obtain victim contact information via Red Bull, it could alert the scam park to the presence of an insider, potentially tracing back to Red Bull and putting him in danger. To stop a six-figure scam or arrest a contact and expose him to risk was simply not worth it.

In less than 24 hours of contact with Red Bull, I had made a decision: to protect him, even though this six-figure scam was about to happen, I could only stand by and watch.

West also told me that, aside from the sting, she didn't think turning Red Bull over to the FBI was a good idea either. She said that if he became an informant for law enforcement, the FBI or Interpol would almost certainly make him stop contacting me or any other journalists. Moreover, the information he provided to the FBI would likely yield results far below his expectations: at most, there would be absent criminal charges against low-level bosses. "If he thinks the FBI and Interpol will come into Laos and take down this den, that's absolutely impossible. No one is coming to save him."

She believed that rather than filing a case against this one scam den, a more valuable approach would be to use all the information Red Bull could provide to tell a larger story: to reveal the true state of the pig-butchering parks, their operational details, and the scale of the industry. Survivors from the parks had described these contents before, but to West's knowledge, no insider had ever leaked documents and evidence in real-time for such a detailed exposé.

West told me that due to the Trump administration's dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development, which had previously funded humanitarian organizations in the region, it had become increasingly difficult to assess the scale of human trafficking behind the scam parks. "The Trump administration's rise to power has cost us all our eyes on the ground there," West said.

All of this allowed criminal groups to continue stealing the wealth of our generation through this system of slavery, as West described, a system that is increasingly taking control of an entire region of the world. "The core of this story is how we have allowed these criminals to take root in Southeast Asia like a rotting cancer," West said, "and how this has destroyed trust between people."

I told Red Bull that for his safety, we could not arrange a sting operation. I also explained that if he wanted to continue being my informant, he might need to temporarily suspend contact with law enforcement. He unexpectedly accepted this decisively. "Okay, let's do it your way," he said.

Soon, Red Bull and I established a fixed communication pattern: we would have a call every morning New York time, which was around 10 PM in Laos, just after he woke up and had half an hour to walk outside the dorm before heading to the cafeteria for dinner. After that meal, he would start about 15 hours of work, with only two breaks for meals.

In our initial calls, he spent most of the time proposing increasingly risky methods for gathering evidence: he wanted to wear a hidden camera or microphone; suggested installing remote desktop software so I could see everything on his computer screen in real-time; proactively offered to install spyware on his team leader's computer—his team leader was also an Indian employee, wearing pilot sunglasses and sporting a short beard, going by the name "Amani"; he even planned to hack into the laptop of Amani's boss, nicknamed "50k," a short, chubby Chinese man wearing tight pants with a tattoo on his chest that Red Bull never managed to see clearly. He believed this spyware might help us collect communication intelligence between 50k and his boss "Alang," whom Red Bull had never seen in person.

For each of these bold ideas, I consulted colleagues and professionals, and their answers were consistent: hidden camera evidence collection requires professional training; the software Red Bull wanted to install on the office computer would leave traceable marks; in other words, these actions were highly likely to get him discovered and potentially killed.

Ultimately, we settled on a much simpler method: during work hours, he would log into Signal on the office computer, send me messages and materials, while setting Signal's self-destruct feature to 5 minutes to cover his tracks. Sometimes, to create a cover and avoid detection, he would start calling me "Uncle," pretending he was just talking to a relative.

We also established a code: one party would send "Red," and the other would reply "Bull," confirming that the account had not been taken over by someone else. Red Bull also came up with a way to change the name and icon of the Signal app on the computer to make it look like a desktop shortcut for a hard drive.

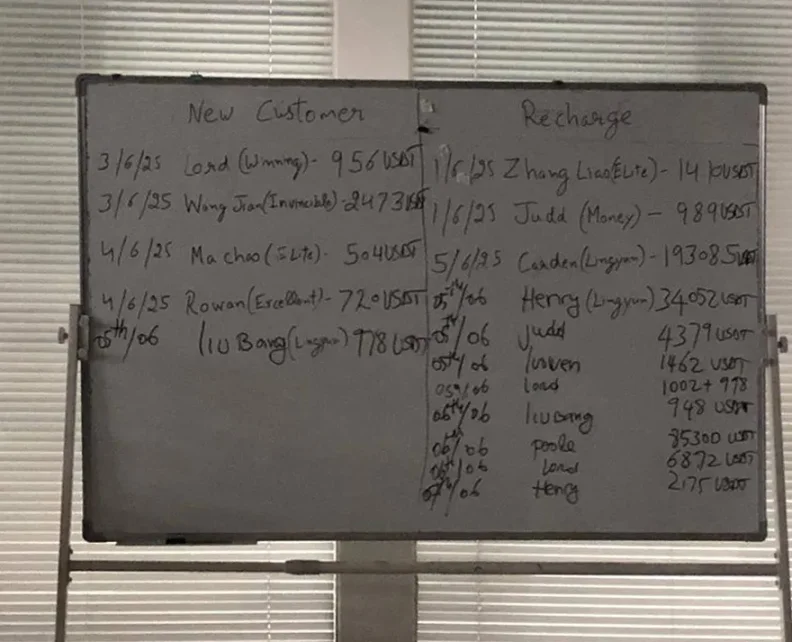

He began sending me a steady stream of photos, screenshots, and videos: a spreadsheet, and a photo of a whiteboard recording his team's work progress, with many members' nicknames next to amounts scammed in the thousands of dollars; a Chinese ceremonial drum in the office that would be struck to celebrate whenever someone successfully scammed over $100,000; pages of chat records posted in the office WhatsApp group, documenting the scam results of Red Bull's colleagues and the desperate replies from victims: "I always dreamed of having a girlfriend like you and then getting married," "Why aren't you replying to me?" "I will always pray for your mother," "Please help me withdraw my money, okay?" "??????" "😭." There was also a video capturing a victim crying in his car, having been scammed out of six figures; this victim sent the video to the scammer, perhaps hoping to evoke a sense of guilt, but instead, the video circulated in the office and became a laughingstock.

Every employee had to report their work progress daily: how many "initial communications" they had initiated, how many "in-depth communications" they had conducted, which were the conversations that could lead to scams. Their group chats were filled with various coded language, such as using "developing new clients" to refer to luring new targets and "re-investment" to refer to victims who fell for the scam again. Each team had performance targets, usually around $1 million per month. Meeting the targets allowed employees to earn the right to take weekends off, eat snacks in the office, and even go to nearby clubs for parties. (Red Bull said that at the parties, the bosses would be active in private rooms with drawn curtains.) Failing to meet the targets resulted in scolding, fines, and being forced to work seven days a week without rest.

A whiteboard in the office recording scam results, with employees' nicknames and team names noted beside them. Provided by Red Bull.

Each employee was also required to submit a mandatory daily schedule, but this was not their night shift life sitting in a fluorescent-lit office sending messages on Facebook and Instagram; rather, it was the schedule of the wealthy single woman they were impersonating: 7 AM "mindfulness yoga and meditation," 9:30 AM "self-care and planning vacations," 2:30 PM "dentist appointment," 6 PM "dinner and chatting with mom."

Sometimes during voice calls, Red Bull would ask me to turn on the video and record the screen. Then he would walk into the cafeteria, pretending to talk to "Uncle," secretly filming the surroundings. I felt as if I was following him through the building: the brightly lit lobby, the stairwell, and rows of expressionless South Asian and African men lining up for food. Once, he even captured footage of the office interior, a huge beige room with rows of desks adorned with red, yellow, and green flags representing each team's scam performance.

A few days later, Red Bull and I upgraded our cover identities; I became his secret girlfriend, messaging him secretly so that if he was discovered using Signal, there would be a more reasonable explanation. Our conversations were sprinkled with heart emojis, calling each other "dear," and ending with "miss you." Eventually, our chat logs almost mirrored the fake romantic scams his team performed daily. But it wasn't long before we found this disguise too awkward and abandoned it.

On another occasion, just as I was about to sleep, Red Bull sent me an unusually sentimental farewell message: "Good night! 🌙 Rest well— you've done enough today. Clear your mind, and face the new day tomorrow with fresh thoughts and calm strength."

Although the text read a bit stiffly, I had to admit that this particularly thoughtful message touched me. In fact, since we started communicating over the past few days, I had been under immense pressure and had hardly slept.

In the following morning's call, Red Bull explained to me the role of AI chat tools like ChatGPT and Deep Search in the scam work at the park: the park would train employees to use these tools to refine their scripts and manage emotions, always having endless sweet talk.

He told me without hesitation that the goodnight message from the previous night was directly copied from ChatGPT. "Everyone here does this; that's how they teach us," he said.

I couldn't help but find it amusing that a warm message from a stranger on the other side of the world could easily touch someone's heart.

From a Boy in an Indian Village to an Anti-Fraud Whistleblower

Every day, during the short few minutes Red Bull took to walk from the dormitory to the office, besides discussing his safety and evidence-gathering strategies, I would ask him how he ended up in this scam park and why he was so determined to expose it all. In hurried snippets of conversation or later in long text messages, he shared with me the story of his 23 years of life.

Red Bull told me that he was born in a mountain village in the disputed region of Jammu and Kashmir on the India-Pakistan border, the eighth of eight children in a Muslim family. His father was a teacher who sometimes worked as a construction laborer, and together with his mother, they struggled to make ends meet by raising dairy cows and selling ghee.

In the early 2000s, when Red Bull was still a child, his family often left the village to seek refuge in northern Kashmir to escape the intermittent conflicts between the Indian army and Pakistan-backed guerrillas. Muslim men in the region were sometimes forcibly conscripted to fight for Pakistan-backed armed forces or transport supplies, only to be labeled as terrorists and killed by the Indian army.

After the conflict subsided, Red Bull's parents sent him to live with his grandparents in Rajouri, a four-hour drive away, hoping that this exceptionally bright and curious child could receive a better education. He told me that his grandparents were very strict with him. In addition to studying, he had to chop wood and fetch water, and the school was six miles from home, which he could only walk to. His shoes wore out, and his feet developed blisters, so he had to tie his pants with a rope as a belt when going to school.

Even so, he said he always maintained a stubborn optimism. "I kept telling myself: even if today doesn't work out, tomorrow will be better," he wrote in a text message.

At the age of 15, his grandparents sent him to live with two teachers who made him work as a servant to pay for his tuition. He would wake up before dawn every morning, clean the house before breakfast, wash the dishes, and then go to school.

He remembers one day, in that house, he was mesmerized watching the family's eldest son play the latest FIFA game on the computer; it was the first time Red Bull had seen a computer. But the next moment, he was scolded and sent back to work. It was from that moment that he developed an obsession with computers. "I felt ashamed and disrespected because I didn't even have the right to touch a computer," Red Bull wrote, "I told myself that one day, I would be the master of that machine."

After enduring a particularly humiliating scolding, Red Bull decided to run away. The next morning, while the family was still asleep, he left and made his way to the city, taking on various odd jobs: cleaning houses, doing construction work, and harvesting rice. For a time, he even went door to door selling Ayurvedic medicine. At night, he self-studied in a rented room. In 2021, he was accepted into the computer science program at the Kashmir Government Polytechnic College in Srinagar, the largest city in the region.

During his university years, the winters in Kashmir were particularly cold, and he slept in a room without proper bedding, often going hungry. A friend taught him how to create Facebook pages for businesses or buy and sell Facebook pages like real estate developers. He tinkered on the school's computer and quickly earned about $200, with which he bought a second-hand Dell laptop—this became his most treasured possession and changed his life.

After three years of studying and working while sending money home, he finally obtained a diploma in computer engineering. He said he was the first person from his village to achieve such a high level of technical education. It was during this time that he developed a stubborn, even slightly angry determination: to rely on himself and carve out his own path in life.

"My parents always advised me to be patient and strong; their words gave me some inner strength, but this battle of life could only be fought by me," he wrote, "No one can truly understand me, but I have never stopped fighting against fate."

A "Job Search" Journey to Hell

Not long after graduating, Red Bull was earning a decent income from creating Facebook pages and websites, with a monthly salary reaching up to $1,000. But he had bigger ambitions, dreaming of working in artificial intelligence or biomedicine, or becoming a white-hat hacker in the cybersecurity industry. (The show "Mr. Robot" had always been his favorite.) He wanted to study abroad but couldn't afford the costs, and his applications for student loans were rejected.

With no other choice, he decided to work for a year or two to save some money. A friend from university told him that there were good job opportunities in Laos. Red Bull began contacting this intermediary, who went by the name Ajaz, claiming to know an agent who could help him find a job as an IT manager in a Laos office, with a salary of about $1,700. For Red Bull, this enticing salary meant he might only need to work for a year before returning to school.

Ajaz had Red Bull fly to Bangkok and then call the recruiting agency from the airport. Red Bull boarded the plane without even knowing the industry of the employer, only that his job would be to assist in managing computers. He remembers the excitement of his first trip abroad filling him as he flew over the Indian Ocean at night, his mind full of hopes for the future.

The next morning in Bangkok, he called the agency, where he spoke to an East African man who brusquely instructed him to take a 12-hour bus ride to Chiang Mai and then a taxi to the Laos border. After arriving at the border, he was required to take a selfie outside the immigration office and send it to the agency. Red Bull complied, and a few minutes later, an immigration officer came out, waved the selfie he had obviously received from the agency, and demanded 500 Thai Baht, about $15. Red Bull paid the money, and the officer stamped his passport, then directed him to the Mekong River to board a waiting boat. This ferry crossed the Mekong River in the section south of the tripoint of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar. This was the Golden Triangle.

Once the boat entered Laos, a young Chinese man on the opposite bank showed Red Bull the same selfie. Without saying a word, he took Red Bull's passport, handed it to the immigration officer, and slipped him some Renminbi. Soon, the passport was returned, stamped with a visa.

The Chinese man stuffed the passport into his pocket and told Red Bull to wait for the East African intermediary. Then he left with Red Bull's passport.

An hour later, the intermediary arrived, driving a white van that took him to a hotel in northern Laos where he would spend the night. Lying on the bed in the empty hotel room, all he could think about was the first formal job interview he would have the next day, filled with anxiety and anticipation. At that time, he was still completely unaware.

The next morning, he was taken to an office, a gray concrete building standing amidst the lush mountains of northern Laos, surrounded by other monotonous buildings. Red Bull nervously sat at a desk while a Chinese man and a translator conducted typing and English tests, which he passed easily. They told him he was hired and then began asking about his familiarity with social networks like Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Red Bull enthusiastically answered all the questions. Finally, they asked him if he understood the nature of the job he was about to start. "Is it as an IT manager?" he asked. They replied no, this time without any euphemisms: what he would be doing was being a "scammer."

It was only at that moment that Red Bull finally understood his situation, plunging into extreme panic. The Chinese boss told him he had to start working immediately. To buy some time, he desperately pleaded to be allowed to rest for a night at the hotel before starting work. The boss agreed.

That night, in the hotel room, Red Bull frantically searched online for information about scam dens in the Golden Triangle. It was only then that he realized how deep the trap he had fallen into was: it was too late; he saw thousands of other Indians like him, deceived and imprisoned in the same way, without passports and with no chance of escape. In this nauseating realization, his parents video-called him, asking if he had gotten the IT manager job. He suppressed his shame and regret, told them he had, forced a smile, and accepted their blessings.

Colorful flags in each team's work area represent whether their scam performance meets the standards. Provided by Red Bull.

A Chinese ceremonial drum stands in the office; whenever an employee successfully scams over $100,000, the drum is struck. Provided by Red Bull.

In the following days, with almost no pre-job training, he was swept into the operations of this scam organization. He later learned that this park was called the Boshang Scam Park. He was trained to create fake accounts, obtain scam scripts, and then began working night shifts, manually sending hundreds of flirty messages each night to lure new victims. After work, he returned to the upper bunk of a six-person dormitory, which was smaller than the hotel room he had stayed in on his first night.

But he said from the very beginning, he was determined to fight against fate again. He discovered that he understood computers better than most of his colleagues, even better than the bosses. Those bosses seemed to only know how to use social media, AI tools, and cryptocurrencies. Within just a few days, he began to fantasize about using his technical skills to secretly gather information about the park and somehow expose it.

Red Bull gradually realized that there were actually no significant obstacles to leaking the secrets of the park. During work hours, the team leader would collect employees' personal phones and put them in a box, strictly prohibiting employees from taking work devices out of the office. But beyond that, the park's monitoring of employees and their personal phones was surprisingly lax.

In Red Bull's view, the bosses seemed to primarily rely on fear and despair to control the victims who had been trafficked, while most of his colleagues appeared to have lost all hope of resistance. "They tell themselves that survival is the only goal, then suppress everything human within them," Red Bull wrote, "empathy, guilt, and even memories of their past selves."

The reason he was able to maintain hope was partly because he felt different from the others. "Most people don't have such skills, tools, or even the inner strength to resist from within," he wrote, "but I can maneuver within this system, observe, collect evidence, names, scripts, routines, and related information."

But sometimes, I still couldn't understand what gave Red Bull the courage to contact me and risk his life, rather than just enduring the contract period. "Perhaps it's for justice, or perhaps out of conscience," he replied, "If there is a God, I hope He can see everything I do. If not, at least I know that in this place that tries to turn people into devils, I have preserved my humanity."

Crisis Looming: Risks of Exposure and Desperate Escape Plans

As time went on, Red Bull sent me more and more materials, and I gradually felt that danger was closing in on him step by step. One day, Red Bull told me that his team leader Amani had questioned him in a calm yet threatening tone about why he was spending so much time outside without developing many new "clients." Amani even suggested that perhaps a beating or a few electric shocks could improve his work efficiency.

Almost at the same time, Red Bull said that new surveillance cameras had been installed in the office, even on the ceilings in front of and behind his desk. I instructed him to immediately stop contacting me from the office; the risks were simply too great now. My editors reached a more decisive conclusion: I had to completely stop the interviews with Red Bull until he gained his freedom.

At that time, Red Bull had already sent me 25 scam scripts and guides in both Chinese and English. These documents analyzed the entire scam process with a level of detail I had never seen before: a list of flirting scripts; how to respond when the target requests a video call, and tutorials on how to stall until the deepfake video model is ready; techniques for complaining about overly cautious financial institutions to prevent victims from being scared off by their bank's warnings.

Perhaps the materials he provided were already sufficient. I followed the editors' advice and told Red Bull that it was time to stop. "Okay, that's it," he said, as straightforward as ever.

A secretly filmed video through a Signal call showing the interior of the cafeteria at the Boshang Scam Park. Red Bull said the food here has a strange chemical taste. If employees violate any rules, even just being late for work or not being in the dorm during roll call, they will be banned from entering the cafeteria.

I told him that now he should do his best to safely endure the remaining six months of his contract, and once he was free, we could reconnect. But Red Bull, once again, had already thought further ahead. He told me that if the interview ended here, he would need to leave immediately.

He shared a long-planned escape plan: to forge a letter from the Indian police claiming he was under investigation in the Jammu and Kashmir region. He would tell his supervisor that if he didn't return, not only would he and his family get into big trouble, but the entire park would also be implicated. He would plead with the boss to let him go home for two weeks to handle this matter, promising to return afterward. He said perhaps the boss would believe this story and let him go.

I thought this plan was completely unworkable and told him so: I warned him that the park's management might discover the document was forged and then punish him. But after I dissuaded him from one risky plan after another, he seemed particularly fixated on this one. I told him to wait, saying I would try to contact someone familiar with escape strategies from the scam park. For example, I knew a Southeast Asian activist who only went by "W" and had experience helping political refugees escape the region.

Just as he walked into the office lobby, Red Bull suddenly switched to cover mode. "It's okay, uncle, don't worry," he said as he passed by the security guard, "Everything will be alright, okay?" Then he hung up the phone.

In our regular conversations, Red Bull had also mentioned another possible path to freedom: if he could come up with about $3,400, he could buy his freedom and go home. He just needed to find a way to get that money.

In an instant, countless thoughts flashed through my mind. First, I felt a glimmer of hope for Red Bull and wanted to help him pay off this ransom. But then I realized that Wired magazine could never pay a source in this way, let alone pay a ransom to a human trafficking criminal group. This idea violated journalistic ethics. Paying sources is generally considered a corrupt practice that creates a conflict of interest and sets an unforgivable precedent. I told Red Bull these thoughts, and he quickly replied that he "completely understood" and had never asked me or Wired to pay this money.

Even so, just the suggestion of this ransom planted a dark thought in my mind that I couldn't shake: What if Red Bull was deceiving me? Initially, after seeing enough evidence to prove he was who he claimed to be—a real victim trapped in a terrifying scam park in Laos—I had set aside my initial doubts. And now, after nearly two weeks of knowing him, this unsettling possibility lingered: What if he was actually an insider in the scam park, and this had all been a scam from the beginning? Just thinking about it made me feel like I was betraying all the trust he had placed in me.

I decided to set aside this doubt, believing he might have ulterior motives while also being more willing to trust that his intentions were sincere.

Meanwhile, a few days later, he brought up the idea of forging documents again, and I suggested once more that he wait for someone like W to help him and not risk implementing this plan. But I could sense his determination was growing stronger by the day. "I have no other choice," he said, "Let's take it one step at a time."

Plan Exposed: Captured, Ransom, and Confession in Despair

Just a few days later, on a Saturday afternoon, I unexpectedly received an email from the Proton Mail account Red Bull had initially used to contact me; he hadn't used that account since we switched to Signal. Like the first email, this one had no subject line.

I opened the email, and fear instantly seized me, my mind going blank.

"They caught me, and now they have taken everything from my phone," the email read, "They beat me, and now they might kill me."

Red Bull had executed his plan to forge the Indian police documents, and now the worst-case scenario seemed to have occurred.

I forced myself to suppress the panic, rapidly thinking of various ways to help. I texted my editors and W, hoping they might have some ideas. Fifteen minutes after sending the first email, I received another email from Red Bull, which was clearer than the previous one: "I am trapped, with no way to escape. They took my personal phone and ID," the email stated, "If you have any way to help me, please do."

Meanwhile, W replied to me on Signal. We had a hurried phone call discussing what we could do to increase Red Bull's chances of survival. I didn't know how Red Bull had sent the email, but W warned me that replying to the email would be very dangerous. His boss already knew he had lied to them to escape. But for now, it seemed they didn't know he had been in contact with a journalist, leaking the secrets of the park.

If they found out, there was no doubt they would kill him. "The methods would be extremely brutal," W said, "He has no chance of leaving this place alive." He suggested I wait for Red Bull to further inform me of his situation and how to communicate safely before taking action.

After a torturous 24 hours, I finally received another email from Red Bull, a long, chaotic message written in a state of emotional distress.

"Last night those people beat me, and now I'm hungry, having eaten nothing. They stopped my card, took my personal phone and everything. Today they will decide how to deal with me. The Indian group leader and everyone are sitting in front of me, asking if I know who they are, then they beat me again and took me back to the office. Today I must admit that everything I did was fake and confess my mistakes. I can't escape from here; I have no money, and I can't even get out the front door. I'm contacting you with the office computer. If you have any way, just email me, and I will check. Tell W to contact me via email. They have been torturing me, and after bringing me back to the office, I can only use the office computer. I hope you are well tonight."

Before I could reply to this email, I received a Signal message: "Red."

"Bull," I replied.

He quickly sent another message, this time very brief: he was locked in a room, and they demanded he find someone to pay 20,000 yuan, about $2,800, to let him go.

In this life-and-death crisis, I couldn't help but think that this might be the final outcome of the scam I had previously suspected: attracting a journalist's attention, drawing him in, making him responsible for a source's safety, and then demanding ransom to save someone.

Regardless, my editors had made it clear that neither Wired magazine nor I could pay Red Bull or his captors any ransom. In fact, they were more suspicious than ever that he might be deceiving me. But I still felt that the more likely truth was that this nightmare was all real.

Red Bull seemed to have regained his phone, likely because they wanted him to find someone to pay the ransom, but I felt that calling him was too risky. I texted him, suggesting he try to communicate with W to see who could help him escape. W was experienced in these matters, and if Red Bull was being monitored, being discovered talking to an activist was far better than talking to a journalist.

I also told Red Bull that while I felt immense sorrow for everything he was enduring, I could not pay the ransom, just as I couldn't pay for his freedom before.

"Okay," Red Bull wrote, "I understand." He asked me to tell W to contact him, and I agreed.

I watched as he set the Signal self-destruct feature to delete messages after just 5 seconds, which showed how worried he was about being closely monitored.

He sent a thumbs-up emoji, and then the message disappeared.

In the following days, I contacted everyone I thought might be able to help Red Bull, even including those who might pay the ransom: Erin West, W, and the head of the nonprofit organization where W worked. But one by one, they all refused—either out of concern for enabling the human trafficking activities of the scam park, or because they suspected Red Bull's story was itself a scam, or both.

Although Red Bull had shown great enthusiasm when he first stepped forward, West now said it sounded like a human trafficking scam she had heard about elsewhere, where fake victims demanded fake ransoms. W had several Signal voice calls with Red Bull, but his extreme panic left him flustered, and he found Red Bull's urgent request for ransom (and promise to pay it back later) very suspicious. "It sounds like a 'give me one Bitcoin, and I'll give you two' scam," W later told me.

But I still felt I had a responsibility to believe everything Red Bull said, assuming it was all true, and to help him escape to the best of my ability within the bounds of journalistic ethics.

On the third day of his kidnapping for ransom, there seemed to be a slight turn of events. I could clearly sense that the monitoring he was under was no longer as strict, perhaps because his captors were gradually losing patience with him. I decided to take the risk of making a phone call. "Things are not good," he said in his usual understated tone, his voice very low, close to the phone's microphone. He said he had a fever, had been beaten several times, slapped, kicked, and was being forced to admit he had forged the Indian police documents. At one point, the boss put a white powder into a cup of water and forced him to drink it. He said that after drinking it, he became unusually talkative and confident, but soon developed red rashes all over his skin. He said sometimes he was sent back to the dorm to sleep, but he hadn't eaten anything for several days and had been deprived of water for long periods.

He wrote to the Indian embassies and consulates across Southeast Asia, but not a single agency responded. "No one is going to help me; I don't know why." A few minutes into the call, his voice finally broke, and I heard suppressed sobs for the first time, revealing his self-pity.

But then he took a deep breath and quickly calmed down. "I want to cry," he said, "but let's see how things go first."

On the fourth day after his first escape attempt was thwarted and he was held for ransom, Red Bull sent me a text saying that things in the park had changed. Everything was unusually quiet, and no one called him to the office. He asked a few colleagues and learned that there were rumors that the Laotian police planned to raid the park. Their Chinese boss had received internal news and had begun to act discreetly.

The next day, the rumors of a raid continued to circulate, and Red Bull received a hopeful message from the Indian embassy in Laos: "Please provide a copy of your passport and work permit," the message read, "The embassy will take necessary action for rescue."

Redemption seemed just around the corner. But in the following days, there was no further communication. The embassy stopped responding to Red Bull's messages. One late night, I tried several times and finally got through to an official at the Indian embassy. He seemed completely unaware of the person we were discussing and repeated the government's vague promises of rescue before hanging up.

Days passed, and the Indian government provided no clear answers, the police raid did not materialize, and no one was willing to pay his ransom. Red Bull seemed to gradually fall into fatalism. One day, I woke up to a series of messages from him, almost like a confession, as if he feared he would die in the room where he was imprisoned and wanted to confess his sins.

"I want to be honest about something. When I first contacted you, I said I had never deceived anyone, which was not entirely true," he wrote. "The truth is, my Chinese boss forced me to pull two people into the scam. I did not do it willingly, and I feel guilty about it every day. That's why I want to tell you the whole truth now."

Later, he revealed more details about the two victims. He scammed one person out of $504 and another out of about $11,000. He told me both of their names. I tried to contact them but couldn't find one, and the other never replied. According to the incentive mechanism of the scam park, Red Bull was supposed to receive a commission from the $11,000 scam amount. But he said that apart from a meager base salary, he had never received any rewards.

Later, I dug out the photo of the office whiteboard that Red Bull had sent me earlier. It clearly showed the Chinese name the park had given him, "Ma Chao," next to the amount of $504. I had completely overlooked this detail, while he had never tried to hide it.

"I entrust you with my most authentic story," Red Bull wrote at the end of his confession, "This is the whole truth."

After ten hazy days, Red Bull told me that he and his colleagues were asked to pack their things. The office computers were boxed up and moved to the dormitory. All employees were to move to a new building a few hundred feet away and were told to continue working in temporary dormitories instead of returning to the office. According to rumors, the police raid was finally coming.

Red Bull said that during this time, he lived in worse conditions than a pig or a dog, isolated by other employees: without bedding, sometimes sleeping on the floor, and only receiving food when someone remembered him, which was often spoiled leftovers. He had lost a lot of weight, felt sore all over, had a fever, and felt like he had the flu.

Even so, Red Bull did not give up and was still thinking about collecting more evidence.

During the office shutdown, work equipment was allowed to be brought into the dormitory. The lax security in the park made Red Bull realize this was an opportunity. One day, while a roommate was asleep, he found the roommate's work phone.

He had previously seen the roommate enter the password from behind, and now he quickly unlocked the phone. Then, Red Bull used WhatsApp's "Linked Devices" feature to link his personal phone with this work phone, allowing him to view internal communications from the scam park. He meticulously recorded the screen, reviewing months of internal conversations and all the chat logs with victims shared by his colleagues.

On another day, he found his work phone in another dormitory. Since his escape attempt had been thwarted, he hadn't touched this phone. He used the same WhatsApp linking method to access the messages on this device with his personal phone. Then, he recorded the screen as he browsed through the chat logs. These videos captured the daily operations of the park over three months. Red Bull sent me clips of these videos, but the complete video was nearly 10GB, far exceeding the data limit he could send from his phone.

Survival in Desperation, Returning Home

A week later, after he and his colleagues moved to the new building, Red Bull sent me a series of dramatically different short videos: in one video, dozens of South Asian men stood outside a high-rise building, lined up by Laotian police in khaki and black uniforms; in another video, a group of similarly situated people sat in rows in the lobby. Red Bull told me that the police raid had finally come, clearing out the scam dens that had not evacuated from the old office area like his boss had. Now, these videos circulated among employees who had narrowly escaped the purge.

While other scam dens in the park struggled to adapt to the new temporary office environment, Red Bull had clearly been suffering in purgatory for weeks. He pleaded with his boss to let him go, saying he was of no use to them anymore. He had no money, and clearly, no one was willing to pay his ransom. In this already crowded temporary building, he was just a burden, taking up space for no reason.

Shockingly, the boss agreed. They did not kill him but told him he could leave.

To gather enough money for his journey home, Red Bull borrowed a few hundred dollars from his brother. Then, he wrote to an Indian acquaintance at another nearby scam park, saying he was going home to visit family but would return soon. He proposed that if this acquaintance could send him money for a plane ticket, he would share the recruitment referral fee with him when he returned. Soon, a few hundred dollars appeared in his account. Red Bull had scammed a scammer and found a way home.

In late July, Red Bull's team leader Amani stopped him outside the dormitory, returned his passport, and told him he could leave. Red Bull said most of his belongings, including his shoes, were still in the dormitory, and he was now only wearing a pair of flip-flops.

Amani, however, said he didn't care. The 50k himself was sitting in an Audi, waiting to take Red Bull to the border of the Golden Triangle. From there, he would be on his own. Wearing flip-flops, he got into the back seat of the car and left.

Later, after Red Bull successfully escaped, he remained haunted by this final humiliation, as if it was more unbearable than all the slaps, kicks, drugs, and hunger he had endured. "I never thought they would treat me like this," he wrote in a text, accompanied by a crying emoji, "They didn't even let me wear my own shoes."

In the days following his arrival at the border, Red Bull traveled by bus and train, even buying an extremely cheap plane ticket that required no fewer than five layovers, finally returning to India. On the way back to his village, he began sending me the WhatsApp screen recordings he had hidden on his phone and smuggled out of the park.

These documents ultimately became the most valuable and unique materials he provided me. A team of reporters from Wired later compiled these materials into a 4,200-page PDF of screenshots and shared it with experts studying the scam park. We found that this document detailed life inside the scam park, listing every successful scam over the past few months, clearly showcasing the scale and hierarchical structure of this scam den. At the same time, the document revealed the mundane lives of the forced laborers who carried out these scams: their daily routines, the fines and punishments they suffered, and the Orwellian rhetoric used by the bosses to manipulate, deceive, and discipline them.

In the end, no one provided Red Bull with the escape help he needed—not the human rights organizations I tried to contact, not the Indian government that promised to take action but did nothing, and not Wired magazine. Red Bull saved himself. And even in the absence of external support and while trapped in desperation, he still managed to collect these materials and hand them over to me, which became the most significant data evidence to date.

Red Bull returned to his homeland, India.

Red Bull's hands were not clean. He admitted to me that under coercion, he had scammed two innocent people. But despite my doubts and those of others I tried to contact on his behalf, his original intention as a whistleblower ultimately proved to be pure.

Now, there is no longer any doubt: Red Bull is real.

On a quiet back street in a city in India, I waited alone, surrounded by dozens of rhesus macaques, some lazily lounging, some grooming each other, and others leaping across balconies and power lines in the neighborhood. Then, the troop scattered into the woods and rooftops as a white SUV turned the corner, drove down the street, and stopped in front of me.

The door opened, and Red Bull stepped out, wearing the same shy smile he had when he first answered my Signal video call. He looked smaller and thinner than I had imagined, but much more spirited than he appeared on the phone screen, wearing a flannel button-up shirt with freshly cut hair. He walked toward me, his smile becoming brighter and less reserved. I extended my hand, and we shook.

Now, he was finally free, and Red Bull allowed me to reveal his real name: Mohammad Muzahir.

Mohammad Muzahir, aka Red Bull, sitting in the car after meeting with a Wired magazine reporter for the first time in India.

"I'm really happy to see you. I've been looking forward to this day, to meet you face to face and share everything," Muzahir said as I helped him check into the hotel, and we sat in the SUV heading to my place, "I'm so excited I can't express it."

From the time Muzahir escaped until our meeting, the past three months had not been easy for him. He was nearly broke and could no longer focus on creating websites and Facebook pages as he had before; he didn't even have a laptop. To survive, he worked as a waiter and did construction work. Besides working odd jobs, applying for jobs and universities abroad (which he still hadn't succeeded in), Muzahir would use his phone, which had cracked screens and was filled with garbled lines, to frantically research information about various scam dens.

During his research, Muzahir discovered that most of the men captured in that raid were later sent back to the Golden Triangle. He believed that the police action was merely for show and had hardly dealt any substantial blow to the local scam dens. He also learned that the scam park that had enslaved him had moved to Cambodia, taking many of his former colleagues with it.

Muzahir always felt guilty about the colleagues he left behind in the park and was tormented by the fact that he had scammed two people. Photo by Saumya Khandelwal.

In an empty lounge in the basement of the hotel where I was staying, we sat down, and Muzahir told me that he only slept three to four hours each night. He said what kept him awake was the knowledge that the scam park he escaped from, along with dozens of others like it, continued to operate in lawless areas of Southeast Asia and was even expanding to other parts of the world. He couldn't help but think of the colleagues he left behind. He also felt deep guilt for scamming two people, even though he kept telling himself that it was the price he had to pay before becoming a whistleblower. He dreamed of earning enough money to find a way to compensate those two individuals. "To be honest, the ending of this story is not beautiful," he said.

Having experienced countless betrayals and having worked in a den where large-scale betrayal was the business model, Muzahir's biggest problem now was his inability to trust anyone. Even when I tried to introduce him to some human rights NGOs and survivor groups, he was very resistant. "These people are just wasting time, giving false hope," he wrote in a text, "I will never easily trust anyone again."

For some reason, I became an exception to his almost universal distrust. But now that we finally met, I felt I had to confess to Muzahir: there were times I didn't trust him either, even when he needed help the most, I foolishly worried that he might be deceiving me.

To my relief, he just smiled. "You did nothing wrong," Muzahir said. He pointed out that if I had paid his ransom back then, he would have left the park early and would not have had the chance to record and share the complete WhatsApp conversation logs from the scam den.

Muzahir is now eager for Wired magazine to publish a complete analysis report of the materials we gathered. I had pointed out to him that after the report is published, the Chinese mafia might retaliate against him in India, and even if he left India as planned and went elsewhere, he might still be in danger. We could conceal his identity, but his team was small, and even if we didn't publish the detailed report of his experiences, his former bosses would likely know immediately who the whistleblower was.

Muzahir responded that he was willing to take that risk to make his story public, including revealing his true identity. After everything he had been through, Muzahir still maintained his idealism; he hoped that his experience could serve not only as a warning but also inspire more people like him to take action.

At the moment he explained this decision, I saw more clearly than ever the motivation that drove him to take all these risks: he was not only speaking to me but also to all those who might choose to resist or become whistleblowers in the ever-growing scam park industry, to the global power structures that enable this industry, to the survivors, and to the hundreds of thousands trapped in this modern slavery system, voiceless.

"If someone sees my story, maybe more Red Bulls will stand up and speak out," Muzahir said with his characteristic shy smile. "When there are countless Red Bulls speaking out in this world, everything will get better."

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。