CBDC, Bank Stablecoins, and Non-Bank Stablecoins: Structural Roles and Institutional Pathways in South Korea.

Table of Contents

CBDC VS Stablecoins

Digitalization of the Dual Currency System

Globalization Trends of Hybrid Structures

Necessity of CBDC

New Paradigm of Parallel Structures between CBDC and Stablecoins

Bank Stablecoins VS Non-Bank Stablecoins

Objectives of Bank Stablecoins

Objectives of Non-Bank Stablecoins

Optimism: Functional Differentiation and Coexistence

Pessimism: Reintegration of Traditional Industries

South Korea's Stablecoin Strategy

Policy Environment and Basic Premises

Policy Judgments on Government Bond-Backed Stablecoins

Cultivation of Bank-Led Stablecoins

South Korea's Response Strategy

Introduction

This report analyzes the structural roles of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), stablecoins issued by commercial banks, and stablecoins issued by non-banks as core monetary tools in the digital currency era, and explores the possibility of their coexistence, proposing an institutional strategy tailored for South Korea. The dual structure of the traditional monetary system (central bank currency + commercial bank currency) continues in the digital age, with the addition of a currency issuance structure from non-bank entities, evolving the digital currency system towards a "three-pillar" model.

Various types of currency exhibit essential differences in terms of issuing entities, technological infrastructure, policy acceptance, and regulatory feasibility, necessitating the design of coexistence policies that allow for functional differentiation and parallel structures, rather than integrating them into a single order. This report examines the public functions and technological limitations that various digital currencies can fulfill through global experimental cases, particularly emphasizing the role of CBDC as a core means of international settlement and protection of monetary sovereignty, the function of bank stablecoins as tools for the digitalization of traditional finance, and the status of non-bank stablecoins as innovative tools for the retail economy and Web3 ecosystem.

Given South Korea's high regard for monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange management, and financial stability, the report proposes a realistic strategy centered on cultivating bank-led stablecoins while limiting non-bank stablecoins to controlled experiments within a regulatory sandbox framework. Additionally, the report suggests a hybrid structure that ensures technological neutrality and interoperability between public chains and private infrastructures, which can serve as a bridge connecting the traditional financial system with private innovation.

By analyzing the institutional pathways and technological infrastructure strategies available to South Korea, this report proposes a policy direction that aligns with global policy orders while ensuring the sustainable development of the national monetary system.

Purpose of the Report and Scope of Discussion

This report aims to analyze the issuance and circulation patterns of digital assets anchored to fiat currency on a global scale and to propose a set of institutional development directions suitable for South Korean policymakers and industries. For readers in other regulatory regions, please refer to the content of this report in conjunction with local policy contexts.

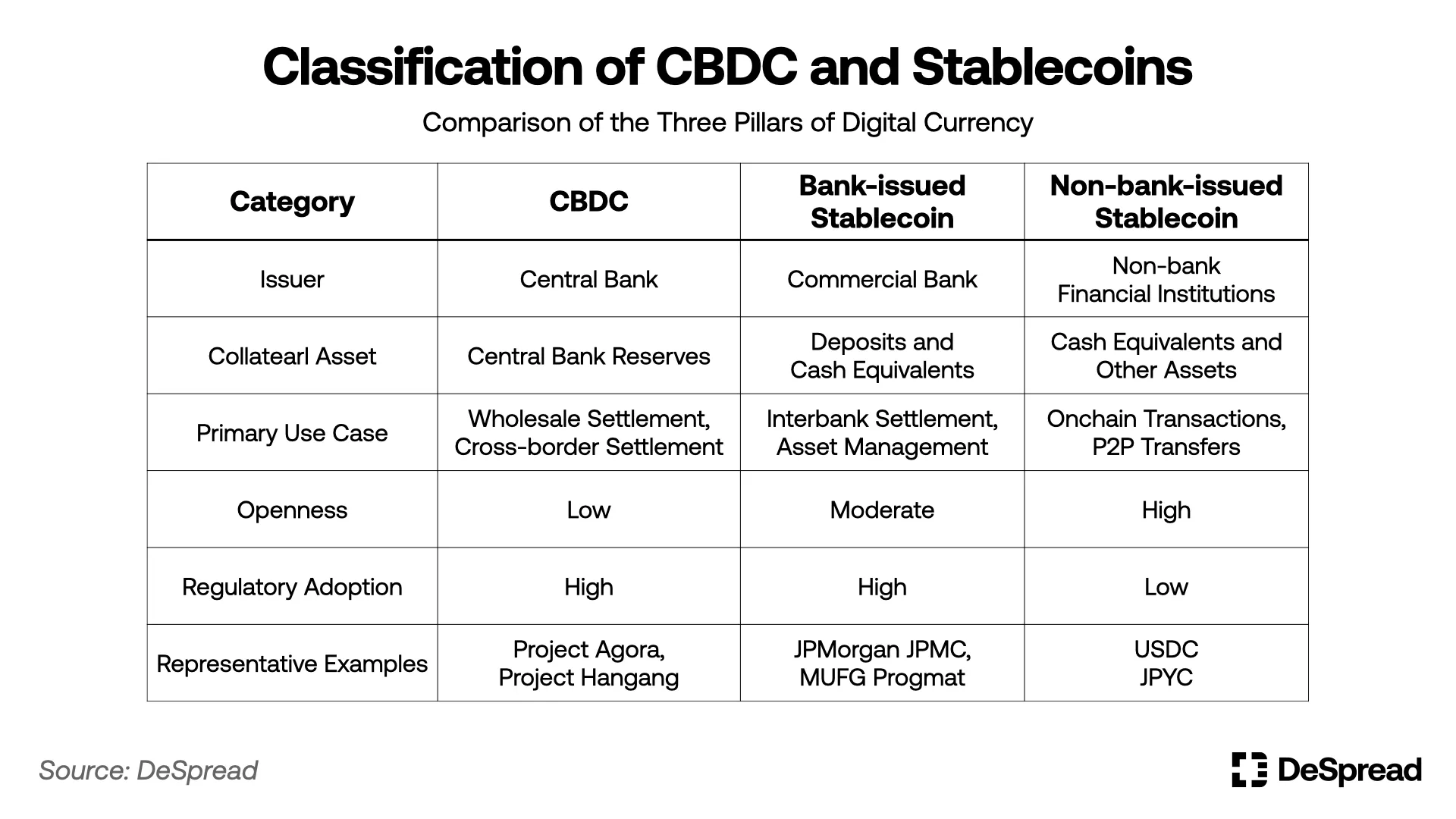

The report first clarifies two commonly conflated concepts: Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) and stablecoins. Although both claim to be pegged to fiat currency at a 1:1 ratio, there are essential differences in their definitions and uses. Based on this, the report further explores how CBDC, bank-issued stablecoins, and non-bank-issued stablecoins can achieve functional complementarity and institutional coexistence as the three pillars of digital currency in an on-chain environment.

Note: The "stablecoins" discussed in this report specifically refer to stablecoins fully backed 1:1 by fiat currency. Other forms of stablecoins, such as over-collateralized, algorithmic, or yield-bearing stablecoins, are not within the scope of this report.

CBDC VS Stablecoins

1.1. Digitalization of the Dual Currency System

The modern monetary system has long relied on a "dual structure," consisting of currency issued by central banks (such as cash and reserves) and currency created by commercial banks (such as deposits and loans). This architecture achieves a good balance between institutional trust and market extensibility. In the digital financial era, this structure continues, represented by Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) and bank-issued stablecoins. With the deepening of digitalization, non-bank stablecoins issued by fintech companies or cryptocurrency enterprises are emerging as the third pillar of the monetary system, further reshaping the digital currency landscape. The current digital currency system can be summarized as follows:

CBDC: Digital currency issued by the central bank, an important tool for implementing monetary policy, ensuring financial stability, and upgrading payment and settlement infrastructure.

Bank Stablecoins: Digital currency issued by banks, backed by customer deposits or government bonds, cash, etc. Deposit tokens are a form of tokenized deposits on-chain at a 1:1 ratio, possessing high legal certainty and regulatory relevance. Additionally, stablecoins can also be issued based on assets other than deposits (cash, government bonds, etc.), including models involving multiple banks.

Non-Bank Stablecoins: Typically issued by entities outside the banking system, such as fintech companies and cryptocurrency enterprises, and circulate as digital currency on public chains. In recent years, hybrid models have emerged that attempt to ensure foundational deposits and institutional acceptance through collaboration with trusts, custodians, and delegated banks.

Note: According to BCG (2025), digital currencies are classified into three categories based on issuing entities and underlying assets: CBDC, deposit tokens, and stablecoins. CBDC is issued by central banks as base money, fulfilling public trust and final settlement functions; deposit tokens are a form of tokenized deposits by commercial banks, highly compatible with the traditional financial system. Stablecoins, on the other hand, are digital assets issued by private entities, backed by fiat currency or government bonds, primarily circulating and settling within decentralized technological ecosystems.

However, this classification is not always adopted by regulatory frameworks in various countries. For example, Japan's regulatory design focuses more on whether the "issuing entity is a bank", rather than the technical distinctions between "deposit tokens and stablecoins." Although the Japanese government clarified in 2023 through amendments to the "Funds Settlement Act" that stablecoin issuance is permitted, qualified issuers are limited to banks, money transfer institutions, and trust companies, with collateral assets initially restricted to bank deposits. Currently, discussions are underway to allow up to 50% of collateral to be Japanese government bonds, indicating the potential for coexistence between deposit tokens and stablecoins. However, from the perspective of issuance authority restrictions, Japan's institutional framework still clearly favors a bank-centric model, differing directionally from BCG's classification based on technological types.

In contrast, non-bank USD stablecoins in the United States have dominated the global market, with strong market demand, making the classification of stablecoins centered on private entities more reflective of reality. Conversely, countries like South Korea and Japan, which have yet to establish any digital token systems, may find it more reasonable to adopt a model that prioritizes the credibility of the issuance structure and its coordination with monetary policy from the early stages of institutional design. This is not merely a comparison of technological types but reflects differences in policy value judgments.

Based on this, this report proposes to redefine digital currencies into three categories: CBDC, bank stablecoins, and non-bank stablecoins, based on policy acceptability, trust mechanisms in the issuance structure, and alignment with monetary policy.

Table 1: Differences between CBDC and Stablecoins

CBDC and stablecoins are not only different in terms of technical implementation but also exhibit essential differences in their roles within the economic system, the feasibility of monetary policy execution, financial stability, and governance responsibilities. Therefore, the two types of digital currencies should be understood as complementary rather than substitutive.

However, some countries are already attempting to redesign this structural framework. For instance, China's digital yuan (e-CNY) serves as a tool for monetary policy execution, India's digital rupee aims to transition to a cashless economy, and the UK's Project Rosalind experiments with a retail CBDC that can directly reach general users.

The Bank of Korea is also experimenting with the boundaries of CBDC and the digitalization of private deposits. The recent "Project Hangang" aims to verify the linkage mechanism between the central bank's institution-specific "wholesale CBDC" and the "deposit tokens" generated by commercial banks converting customer deposits at a 1:1 ratio. As part of the CBDC issuance experiment, this project aims to achieve digital management of commercial bank deposits, which can be interpreted as the South Korean government attempting to integrate deposit digitization into the CBDC system, avoiding the separate institutionalization of private digital currencies.

On the other hand, in April 2025, major commercial banks in South Korea (KB, Shinhan, Woori, Nonghyup, Corporate Bank, and Waterworks) and the Korea Financial Settlement Institute are advancing the establishment of a joint venture to issue a Korean won stablecoin. This is a private digital currency experiment on a different track from deposit tokens, indicating that the boundaries between deposit tokens and bank-issued stablecoins may become increasingly important in future institutional discussions.

1.2. Globalization Trends of Hybrid Structures

Major countries such as the United States, Europe, and Japan, as well as international organizations like the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), are focusing on the digital inheritance of the dual currency structure. In particular, recent collaborations among large U.S. banks such as Bank of New York Mellon, Bank of America, and Citibank are researching wholesale stablecoin projects, proposing new infrastructures that support real-time interbank payments and collateral settlement without central bank intervention.

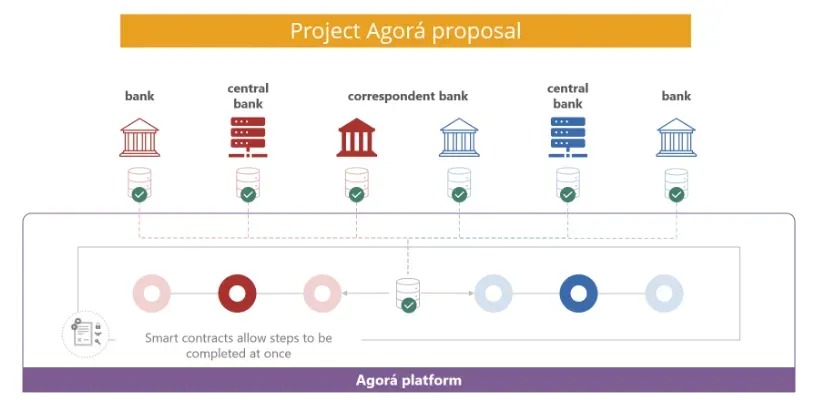

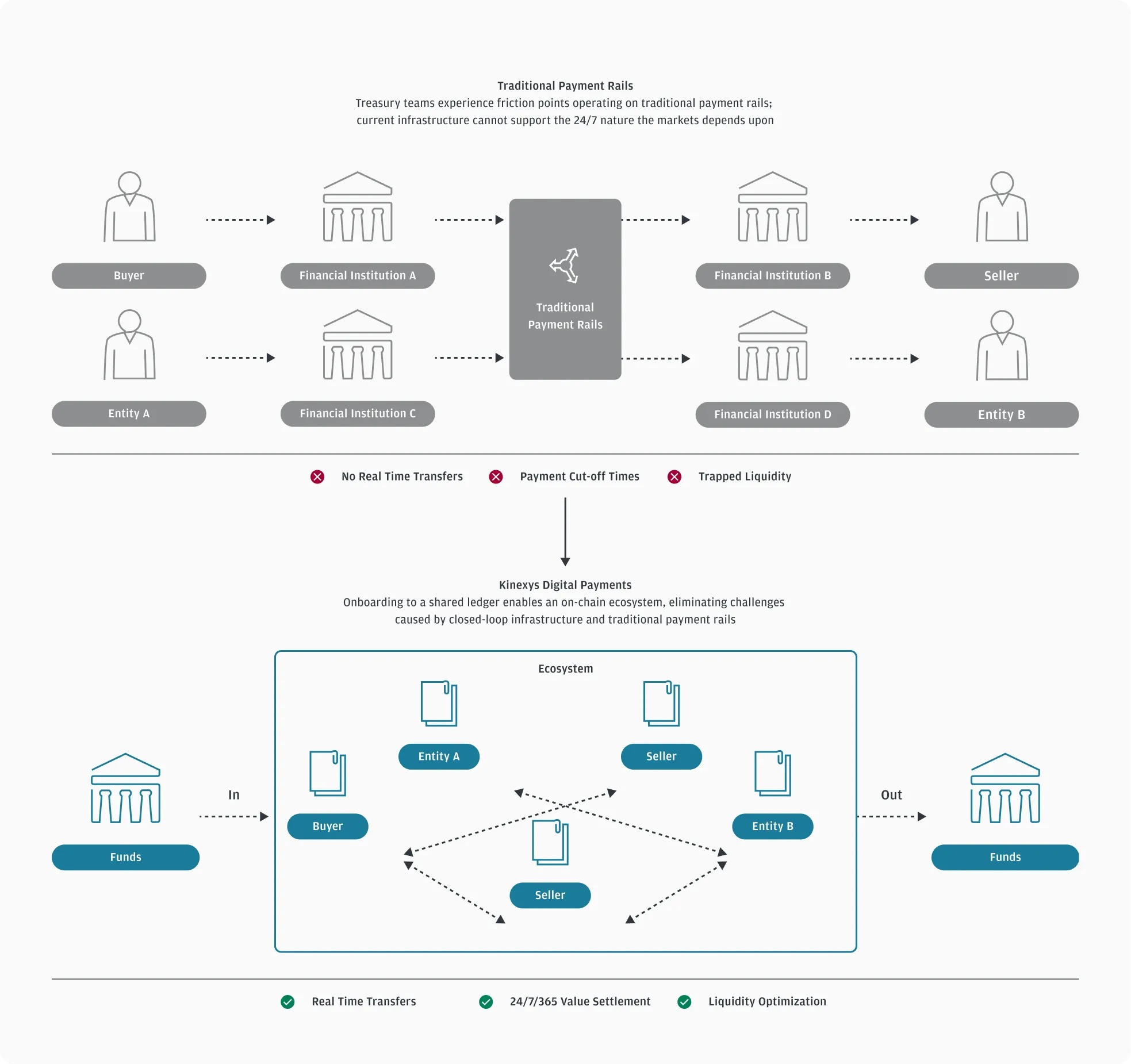

According to the BCG (2025) report, when stablecoins meet regulatory requirements, especially in countries where CBDC is difficult to launch in the short term, privately-led wholesale digital payment infrastructures can play a substitute role. This can be evidenced by cases such as JPMorgan's "Kinexys," Citibank's RLN, and Partior, which achieve high credibility digital settlement without CBDC.

1.3. Necessity of CBDC

In the context of growing recognition that wholesale stablecoins issued by banking financial institutions can construct efficient payment and settlement systems, questions are being raised about the necessity of CBDC in wholesale payments and inter-institutional settlements.

"Is CBDC still necessary?"

In response to this question, the author's answer is "yes." The limitations of private models are not only confined to technological completeness or commercial coverage but also fundamentally constrained in their ability to fulfill public functions such as monetary policy, legal status, and neutrality in international settlement.

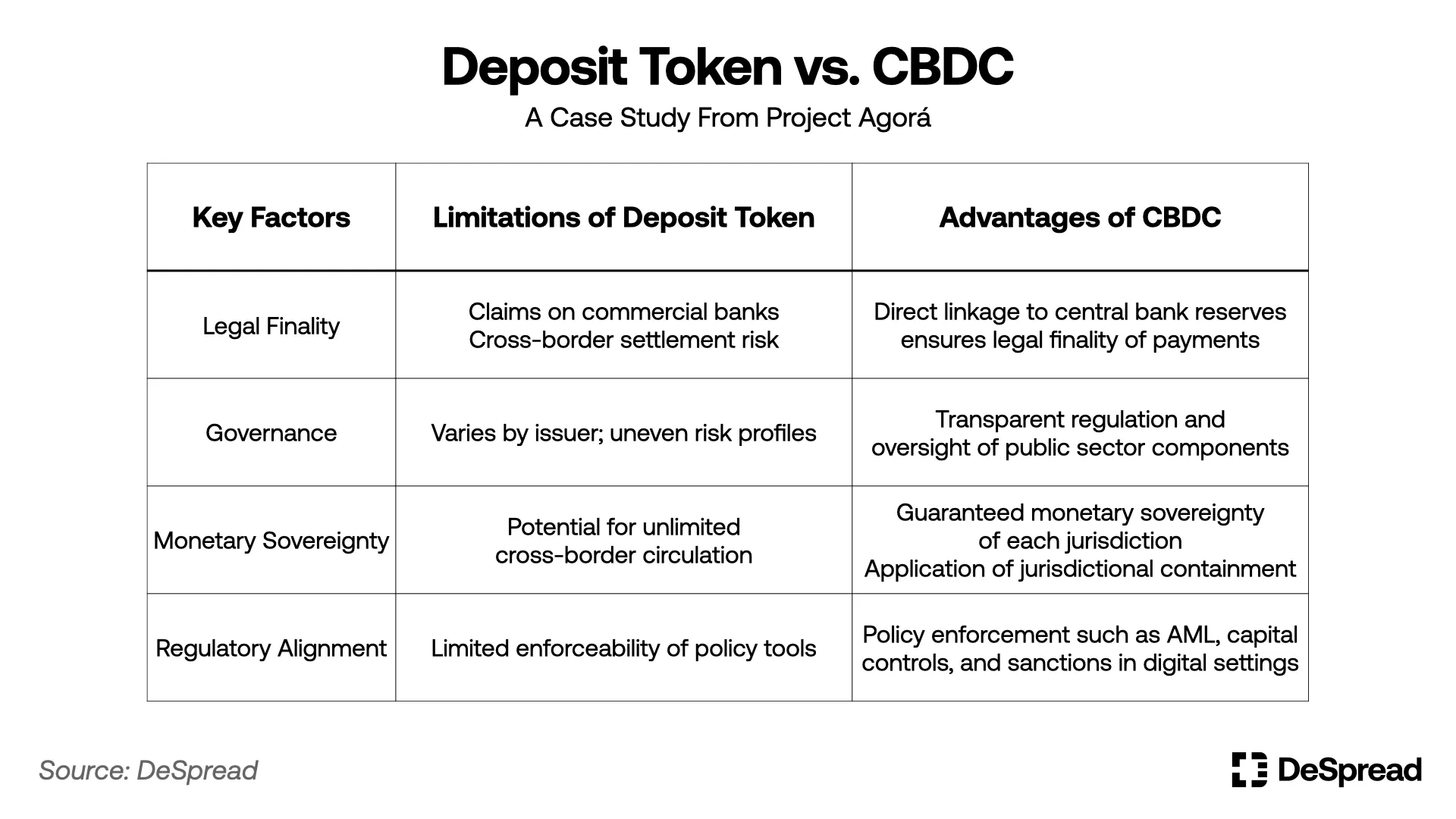

A representative case for systematically validating this through policy is Project Agorá (2024), initiated by the BIS, the European Central Bank (ECB), the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and seven central banks in collaboration with several international commercial banks. This project experimented with the parallel use of CBDC and deposit tokens in cross-border wholesale payment systems. The report aims to enhance the interoperability of public money (CBDC) and private money (deposit tokens) while exploring design principles that can ensure the independence and regulation of national monetary systems. Through this experiment, the BIS implicitly revealed the following policy insights:

Legal Finality Differences: CBDC, as a liability of the central bank, inherently possesses legal finality in settlements. In contrast, deposit tokens essentially represent a claim against commercial banks, which may introduce legal uncertainties in cross-border transactions, leading to settlement risks.

Asymmetry in Governance Structures: CBDC operates under publicly transparent rules and regulatory frameworks, while private tokens exhibit significant differences in technical architecture and governance models due to varying issuers, creating institutional risks in multi-currency, multilateral settlement networks.

Monetary Sovereignty and Judicial Limitation Mechanisms: To safeguard national monetary sovereignty, the Agorá project adopted a principle of judicial jurisdiction isolation, restricting the use of deposit tokens within the domestic financial system and prohibiting direct cross-border circulation, thereby avoiding the chaotic spread of private currencies that could impact national monetary policy.

Regulatory Coordination and Policy Linkage: The BIS focused on how to embed policy tools such as anti-money laundering, foreign exchange controls, and capital flow regulations into digital payment networks. CBDC, as a public asset, has a natural advantage in institutional linkage and regulatory integration, significantly outperforming private token solutions.

Table 2: The Necessity of CBDC Proposed by Project Agorá

Figure 1: Project Agorá

Ultimately, the significance of Project Agorá lies in designing a dual structure where CBDC is responsible for public trust and regulatory coordination in the international digital payment system, while deposit tokens facilitate agile trading interfaces among enterprises, thereby clearly distinguishing their respective roles and limitations.

For South Korea, which is highly sensitive to monetary sovereignty, this structural design is particularly important. The Bank of Korea also participated in Project Agorá, experimenting with digital settlement based on deposit tokens. On May 27, during the "8th Blockchain Leaders Club," Bank of Korea Vice Governor Lee Jong-ryeol emphasized: "Protecting monetary sovereignty from infringement is the core of Project Agorá. The design of South Korea's deposit tokens ensures they will not be used directly in other countries," indicating that South Korea recognizes the importance of protecting its monetary sovereignty principles within the digital settlement structure, beyond merely introducing technology.

If Project Agorá empirically demonstrated the necessity of CBDC as a means of international settlement and its coexistence structure with deposit tokens, then the 2025 collaboration between the BIS and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Project Pine proves that central banks can digitize monetary policy execution and liquidity supply functions through CBDC.

Project Pine designed a structure where central banks automatically execute conditional liquidity supply using digital government bonds as collateral through smart contracts. This experiment not only involves digital currency transfers but also showcases how central banks can directly adjust the money supply, injecting or withdrawing liquidity in real-time, and automating these functions on-chain.

This transcends indirect policy signaling methods such as benchmark interest rate adjustments, suggesting new possibilities for implementing central bank policy execution through smart contracts and "coding" the governance of the financial system. In other words, CBDC is not merely a payment settlement tool but also a foundational infrastructure for the precise and transparent digitalization of central bank monetary policy.

1.4. A New Paradigm of Parallel Structures between CBDC and Stablecoins

We need to view the parallel structure of CBDC and stablecoins as a new paradigm. CBDC should not be seen simply as a "public stablecoin," but rather as a core pillar for policy execution, settlement infrastructure, and system trust-building in the digital financial era; private stablecoins should be regarded as flexible and rapid financial assets catering to general user needs.

The key issue is not "why both are needed." We have been operating under a dual structure of central bank money and commercial bank money, and even in the era of digital assets, this structure will only change at the technical level and be inherited. Therefore, we anticipate that the parallel structure of CBDC and private stablecoins will become the new monetary policy order in the digital age.

Bank Stablecoins VS Non-Bank Stablecoins

As the parallel structure of CBDC and private stablecoins gradually establishes itself as a policy order, we can further refine the upcoming discussions. An important point of contention regarding the internal structure of private stablecoins has emerged: should bank stablecoins and non-bank stablecoins develop in parallel, or should only one be chosen for institutionalization?

Although both types have a structure pegged to fiat currency at a 1:1 ratio, there are clear distinctions in terms of issuing entities, policy acceptance, technical implementation methods, and usage scenarios. Bank stablecoins are digital currencies issued by regulated financial institutions based on deposits or government bonds, with limited use of public chains. In contrast, non-bank stablecoins primarily circulate on public chains, mostly issued by Web3 projects, global fintech companies, and cryptocurrency enterprises.

2.1. Objectives of Bank Stablecoins

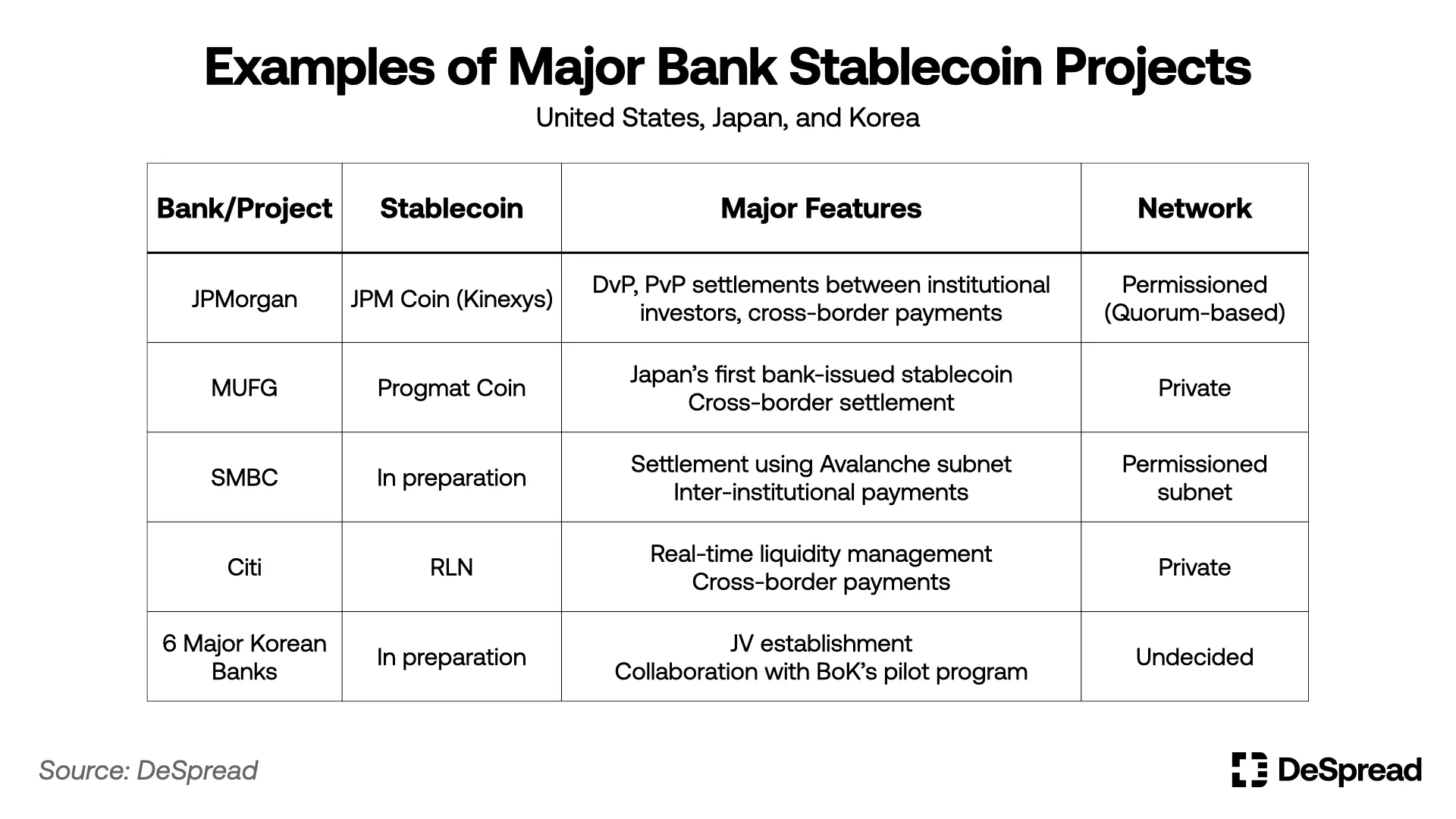

Bank stablecoins replicate the role of deposits within the traditional institutional financial system on-chain. Examples include JPM Coin from JPMorgan, Progmat Coin from Japan's MUFG, yen stablecoins from Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, and RLN from Citibank, all of which operate within regulatory frameworks concerning AML, KYC, depositor protection, and financial soundness.

These stablecoins serve as digital cash that meets both institutional stability and the automation flexibility of smart contracts in scenarios such as delivery versus payment (DvP) and funds versus payment (FvP) settlements among institutional investors, trade finance clearing, and portfolio management, characterized by legal certainty, KYC-based participant control, and potential linkage to central bank reserves.

Particularly, the cases of JPMorgan's Kinexys and Citibank's RLN operate on permissioned networks, allowing only pre-verified institutions to conduct transactions based on identity, transaction purpose, and source of funds, thus providing clear legal liability structures and regulatory responses. Additionally, these networks have designed deposit-backed stablecoins to achieve real-time payments and settlements through centralized node structures and interbank consensus protocols, enabling on-chain financial activities to avoid the volatility and regulatory risks of public chains.

Figure 2: Structure of JPMorgan Kinexys

Commercial banks in major countries such as the United States, Japan, and South Korea are actively issuing or promoting the introduction of deposit-based stablecoins. In addition to deposit backing, trends can also be found in various countries for bank-issued stablecoins backed by government bonds and cash equivalents such as money market funds. In the United States, large bank alliances like Zelle and The Clearing House are discussing the joint issuance of stablecoins, indicating the spread of the regulated stablecoin model issued by commercial banks. The Japanese Financial Services Agency is studying the possibility of increasing the proportion of government bonds in the collateral assets of stablecoins, considering a cap of up to 50%. In South Korea, six major banks, including KB Kookmin, Shinhan, Woori, Nonghyup, Corporate Bank, and Waterworks, are jointly establishing a legal entity to issue a Korean won stablecoin, which runs parallel to the Bank of Korea's wholesale CBDC experiment (Project Hangang), suggesting a coexistence pattern between deposit tokens and stablecoins.

This trend indicates that putting deposits on-chain is no longer merely a technical experiment but is introducing substantial automation into the financial payment and settlement structure within the institution. At the same time, major countries are expanding the types of collateral assets acceptable for bank stablecoins, incorporating cash equivalents to strengthen the liquidity supply function of stablecoins within the regulatory framework.

Table 3: Major Bank Stablecoin Cases

2.2. Objectives of Non-Bank Stablecoins

Non-bank stablecoins are a new type of monetary user interface that has emerged to achieve technological innovation and global scalability. Typical representatives include Circle's USDC, PayPal's PYUSD, and StraitsX's XSGD, which are widely used in e-commerce payments, DeFi, DAO rewards, game item trading, P2P transfers, and other small payment and programmable financial environments. They trade freely on public chains, providing accessibility and liquidity to users outside traditional financial infrastructure. They play a role as standard currencies, especially in the Web3 and DeFi ecosystems.

Within the non-bank stablecoin ecosystem, there is also differentiation: some entities pursue disruptive innovation on public chains, detached from the existing financial system; others aim to integrate into the institutional framework while accepting regulation. For example, issuers like Circle are actively seeking to integrate into the traditional financial system through preparations for MiCA licensing and cooperation with U.S. regulators; on the other hand, there are also experimental models centered around decentralized communities.

Therefore, the field of non-bank stablecoins is a coexistence area that embodies innovation and institutionalization, and future policy design and market regulation will significantly influence the balance between the two.

2.3. Optimism: Functional Differentiation and Coexistence

Regarding whether bank and non-bank stablecoins can substitute for each other, it is more appropriate to consider this from the perspectives of politics, policy, and industrial strategy rather than merely from a technical standpoint. The two models have different institutional constraints and application scenarios, and thus the prospect of achieving coexistence under the premise of functional differentiation is gradually gaining recognition in policy circles and the market.

Bank stablecoins, relying on their legal certainty and regulatory compliance, primarily serve areas such as inter-institutional settlement, asset management, and wholesale payments. JPMorgan's Kinexys has been operational for over four years, while Citibank's RLN and MUFG's Progmat Coin are also in the practical validation stage.

Non-bank stablecoins are more suitable for scenarios such as small payments, global retail services, on-chain incentive systems, and decentralized applications (dApps), and have become the de facto universal currency standard within the public chain ecosystem.

Non-bank stablecoins are key tools for promoting digital financial inclusion and innovation. Compared to the identity verification, residency information, credit history, and minimum deposit thresholds required for bank stablecoins, public chain stablecoins can be used with just a digital wallet, making them highly attractive to the "unbanked." Therefore, non-bank stablecoins provide the only scalable financial access outside the traditional financial system and serve as an important bridge for building inclusive finance and technological democratization.

The fact that bank stablecoins are not issued on public chains reflects the regulatory motivation for institutional exclusion of non-bank stablecoins operating on public chains. For regulators, untraceability, anonymity, and the lack of control over funding inflows and outflows (off-ramps) are core compliance risk factors. Ultimately, digital currencies acceptable within the institutional framework must possess a certain degree of programmable control and export control functions. The maximalist logic of public chains, such as resistance to censorship, will inevitably conflict with the realities of financial regulatory order.

Even so, the non-bank stablecoin market is composed of both technology entities pursuing disruptive innovation and corporate entities seeking stability through regulatory acceptance, indicating that the gradual institutionalization and experimental evolution of the fintech industry are advancing in parallel.

The recently passed procedural vote in the U.S. Senate on the GENIUS Act is one of the U.S. government's efforts to institutionalize this trend. The bill allows for the issuance of non-bank stablecoins under specific conditions, leaving room for discussion on market access for innovative enterprises within an institutional framework. Circle is also attempting to shift towards a regulatory-friendly model through the MiCA licensing process and by accepting oversight from the U.S. SEC; Japan's JPYC is collaborating with MUFG to advance the transition from prepaid payment methods to electronic payment methods. These developments indicate that non-financial entities also have the potential to gradually enter the institutional track.

Non-bank stablecoins that utilize smart contract programming to implement functions such as AML, KYC, regional restrictions, and transaction conditions have the potential to coordinate the openness of public chains with institutional system requirements. However, the technical complexity of smart contracts and regulatory concerns regarding public chains remain unresolved issues. In this context, public chain stablecoins aimed at being "accessible to anyone and compliant" are also receiving significant attention.

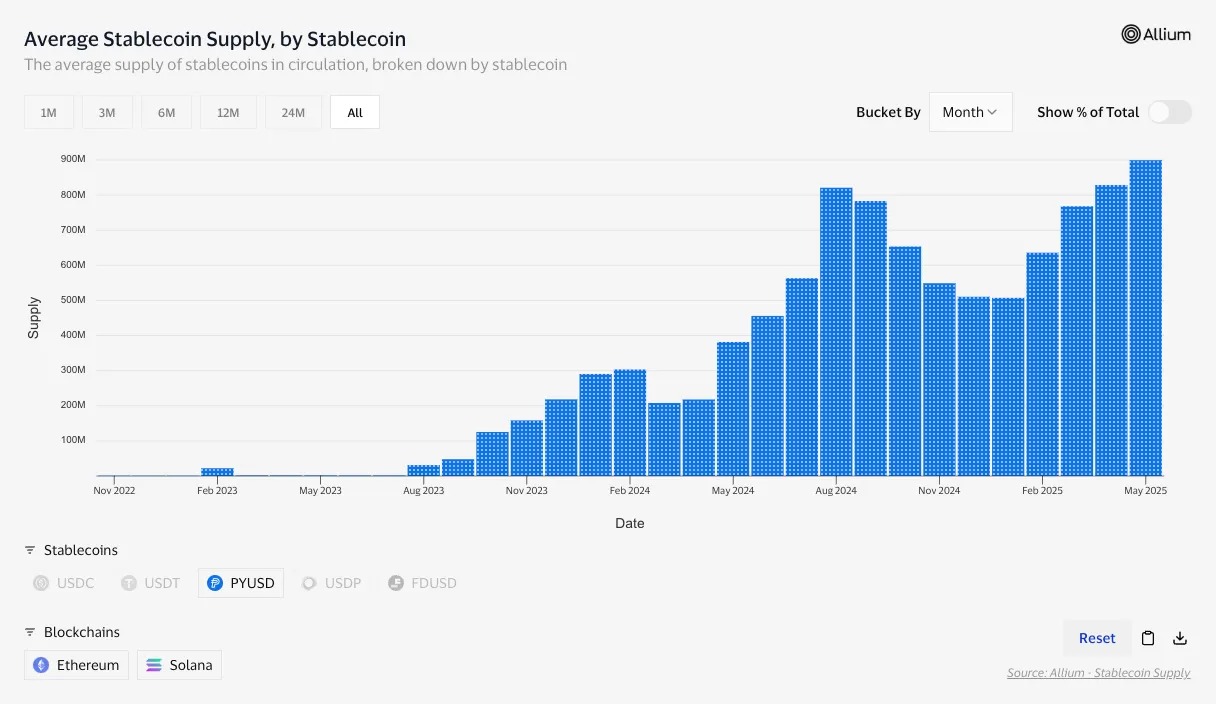

PayPal and Paxos's PYUSD is an example of achieving this goal. PYUSD circulates on public chains such as Ethereum and Solana while coordinating regulatory compliance and openness through Paxos's 1:1 dollar-backed reserve management and PayPal's KYC and transaction monitoring. Since 2024, PYUSD has expanded its influence in DeFi and the retail economy, demonstrating the potential of regulatory-friendly stablecoins.

Figure 3: PYUSD Supply

In May 2025, during a policy discussion at the South Korean National Assembly, the Director of the Financial Consumer Agency, Yoon Min-seop, emphasized that "the innovation of stablecoins is realized through the participation of diverse entities such as fintech and IT companies," and proposed a multi-layered institutional strategy. Additionally, the exploration of blockchain-based payment methods by South Korean fintech companies like KakaoPay and the Financial Services Commission's promotion of stablecoin regulatory discussions further confirm this trend.

In this context, the key point is that non-bank stablecoins do not conflict with or serve as substitutes for the institutional system; rather, they fill the gaps that the existing financial system has yet to encompass, demonstrating the possibility of coexistence. Particularly, their inclusivity for the unbanked, practical applications in the public chain-based Web3 ecosystem, and rapid, low-cost global payment methods cannot be achieved solely through bank stablecoins. Therefore, the two are results of functional differentiation in their most suitable roles, forming a structure of balance and collaboration rather than competition.

2.4. Pessimism: Reintegration of Traditional Industries

There is also a somewhat pessimistic attitude regarding the ongoing possibility of "functional coexistence." After all, many technologies that initially sparked innovation in niche markets often get gradually integrated and subsumed by traditional industries during their development. Traditional enterprises have indeed begun to take the stablecoin market seriously and will not stand idly by.

Large U.S. banks have initiated preliminary discussions around the joint issuance of stablecoins through Zelle and The Clearing House. This aligns with the potential passage of the Genius Act, aiming to preemptively mitigate potential losses from foreign exchange fees, retail payment fees, and the loss of user wallet dominance by issuing their own stablecoins strategy.

In this scenario, even if non-bank stablecoins achieve success in terms of technical advantages or user diffusion, they may ultimately face the risk of being absorbed or marginalized by bank-dominated infrastructures. Particularly, banks can use central bank reserves as collateral for stablecoins, which may give them a competitive advantage in terms of credibility and efficiency compared to stablecoins based on general collateral. In other words, public chain-based stablecoins face structural disadvantages in terms of institutional networks and collateral capabilities.

Although Visa, Stripe, and BlackRock do not directly issue stablecoins, they integrate USDC into payment networks or through their own tokenized funds (such as BUIDL), thereby absorbing the technology and functions of the stablecoin market into existing financial infrastructures, redefining digital currency innovation in a form suitable for institutional frameworks. This is a strategy that maintains the stability and credibility of traditional finance while leveraging the potential of stablecoins.

The aforementioned trend is clearly reflected in the case of StraitsX's XSGD. Although the Singapore dollar-based stablecoin XSGD is issued by a non-bank financial institution, it is backed 1:1 by deposits at DBS Bank and Standard Chartered Bank and operates on a closed network infrastructure based on Avalanche Subnet.

Subnet: An enterprise-level network structure that allows for comprehensive customization regarding openness, consensus mechanisms, privacy levels, etc., specifically designed to meet regulatory compliance.

Notably, XSGD enters the public chain through Avalanche's C-chain and circulates across various networks, benefiting from Singapore's open policy environment. It is expected that a similar structure will be more challenging to apply in regulatory-conservative countries, where not only the issuance structure but also the circulation channels may be restricted to regulated permissioned structures. Ultimately, while XSGD symbolizes a compromise balance between institutional systems and technology, in more conservative countries, the advantages of commercial bank models may be further solidified due to practical constraints.

JPMorgan clearly demonstrates through Kinexys a case where asset management and settlement ultimately converge within a bank-controlled digital financial network. BCG's analysis also suggests that public chain-based stablecoins face structural limitations that make them difficult to regulate, and only models based on financial institutions can sustain themselves long-term within institutional frameworks.

Although Europe's MiCA is formally open to all issuers, in practice, due to capital requirements, collateral management, issuance limits, and other factors, it has created a structure that makes it difficult for entities outside financial institutions to enter the institutional system. As of May 2025, there are not many cases formally registered as electronic money tokens, aside from Circle's ongoing preparations for licensing.

In Japan, the revised Payment Services Act of 2023 restricts the issuance of electronic payment-type stablecoins to banks, trust companies, and money transfer businesses, while tokens based on public chains can only circulate on certain exchanges and cannot gain official recognition as payment methods.

The "programmable regulatory-compliant stablecoin" model mentioned in the optimistic view, while seemingly capable of increasing acceptance within institutional frameworks, requires resolving complex institutional issues such as international regulatory coordination, legal acceptance of smart contracts, and risk liability attribution to be practically realized. Particularly, even if such a design becomes possible, regulatory agencies are likely to regard the credibility, capital strength, and controllability of the issuing entities as core standards.

Ultimately, the non-bank stablecoins that can be accepted by regulators are likely to boil down to "private entities operating like banks," in which case the innovations originally provided by public chains, such as decentralization, inclusivity, and resistance to censorship, will inevitably be diluted. In other words, the optimistic view that functional coexistence will be long-term guaranteed may be overly idealistic, and the digital currency infrastructure may ultimately be reduced to a reintegration centered around entities with scale, trust, and institutional guarantee capabilities.

Korean Stablecoin Strategy

3.1. Policy Environment and Basic Premises

South Korea is a country with strong policy priorities regarding monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange management, and financial regulation. The central bank-centered interest rate-based monetary policy has always operated as a core mechanism for effectively controlling private liquidity, with the Bank of Korea emphasizing predictability and monetary stability through policy interest rates. In this structure, concerns have been raised that the emergence of new forms of digital liquidity may challenge the monetary policy transmission mechanism and the existing liquidity management system.

For example, stablecoins issued by non-bank entities backed by government bonds, while not based on central bank-issued base money (M0), may create a money-creating effect in the private sector by fulfilling monetary functions on-chain. If these digital cash equivalents circulating outside the institutional system are not captured by monetary supply indicators (M1, M2, etc.) or affect the interest rate transmission path, policymakers may view them as "shadow liquidity."

Concerns about this policy risk have repeatedly emerged internationally. The FSB (2023) points out that the disorderly proliferation of stablecoins may threaten financial stability, particularly highlighting risks such as cross-border liquidity transfer, evasion of AML/CFT regulations, and the inefficacy of monetary policy. The BIS (2024) analysis also suggests that in some emerging countries, stablecoins may trigger informal dollarization and reduce the effectiveness of monetary policy due to outflows from bank deposits.

In response, the U.S. has adopted a pragmatic institutionalization strategy through the Genius Act. This act allows for the issuance of private stablecoins but proposes a conditional licensing structure through high credit collateral requirements, federal registration obligations, and qualification restrictions. This does not ignore the warnings from the FSB and BIS but represents a strategic response to absorb risks within a regulatory framework.

The Bank of Korea has also expressed a clear stance on such policy risks. At a press conference on May 29, 2025, Governor Lee Chang-yong mentioned that "stablecoins are privately issued currency substitutes that may undermine the effectiveness of monetary policy," expressing concerns that won-based stablecoins could lead to capital outflows, damage trust in the payment settlement system, and facilitate evasion of financial regulation. He emphasized that "it should first start from a regulated banking sector."

However, the Bank of Korea has not imposed a complete ban but manages and reviews the institutional direction under conditions where risks can be controlled. In fact, apart from CBDC, the Bank of Korea is also promoting payment experiments based on deposit tokens issued by commercial banks (Project Hangang), conditionally accepting privately led digital liquidity experiments.

In summary, stablecoins may serve as a new variable in monetary policy, and the vigilance of international institutions and Korean authorities is not about the technical possibility itself but about how and under what conditions this technology can be accepted within the monetary system. Therefore, the Korean stablecoin strategy should not be an unconditional opening or a technology-centered design but should construct a structure that accepts institutional systems as a premise while concurrently designing policy and technical prerequisites.

3.2. Policy Judgments on Government Bond-Backed Stablecoins

3.2.1 Relationship with Monetary Policy

Stablecoins issued against cash equivalents such as government bonds may superficially appear to be digital currencies based on safe assets, but from a monetary policy perspective, they may function as a privately issued currency structure that central banks cannot directly control. This goes beyond merely serving as a payment method and may create effects that bypass base money (M0), generating liquidity close to broad money (M2).

The Bank of Korea typically guides commercial banks' deposit rates and credit supply by adjusting the benchmark interest rate, thereby indirectly influencing the structure of broad money (M2). However, cash-equivalent collateralized stablecoins may not follow this monetary policy transmission path, forming a mechanism for non-bank entities to directly supply liquidity to the private economy through digital assets. Particularly, in this process, they are not constrained by traditional monetary management tools such as capital regulation, liquidity ratios, and reserve requirements, posing a structural threat from the central bank's perspective.

More importantly, government bonds are originally a means to settle already issued liquidity through government fiscal policy. Using them as collateral to allow private issuance of another form of liquidity (stablecoins) means creating a secondary generation structure of non-central bank-issued currency, effectively approaching the result of "double monetization." Consequently, liquidity within the market may expand independently of the monetary authority's interest rate signals, potentially weakening the transmission power of the benchmark interest rate.

The BIS (2025) analysis confirms that funds flowing into stablecoins caused the yield on U.S. short-term government bonds (3-month bonds) to drop by 2-2.5 basis points within ten days, while outflows led to an increase of 6-8 basis points, exhibiting an asymmetric effect. This indicates that in the short-term funding market, the liquidity flow of stablecoins alone may create an interest rate before the central bank's interest rate policy, potentially leading to a situation where monetary policy centered on the benchmark interest rate cannot form a leading influence on market expectations.

This structure may also affect real interest rates. If the liquidity generated by stablecoins begins to have a substantial impact on asset prices and short-term interest rates within the financial system, the effectiveness of benchmark interest rate adjustment policies will be weakened, and the central bank's monetary policy will no longer be a "leading interest rate determiner" but may become a "market responder."

However, it is also difficult to conclude that all government bond-backed structures will immediately render monetary policy ineffective or pose a serious threat. In fact, the U.S. Treasury explained in April 2025 that it views this as a "digital conversion of existing monetary assets," asserting that it will not affect the total money supply. Government bond-backed stablecoins may produce different effects depending on their operational structure and policy environment, thus requiring precise evaluation based on structural context rather than blanket judgments.

Therefore, government bond-backed stablecoins possess a dual structure of both risk and practicality. Whether they are accepted by policy depends on how their structure connects with the existing monetary system and whether they can be designed in a way that does not undermine the predictability and credibility of policy tools.

3.2.2. Global Comparison

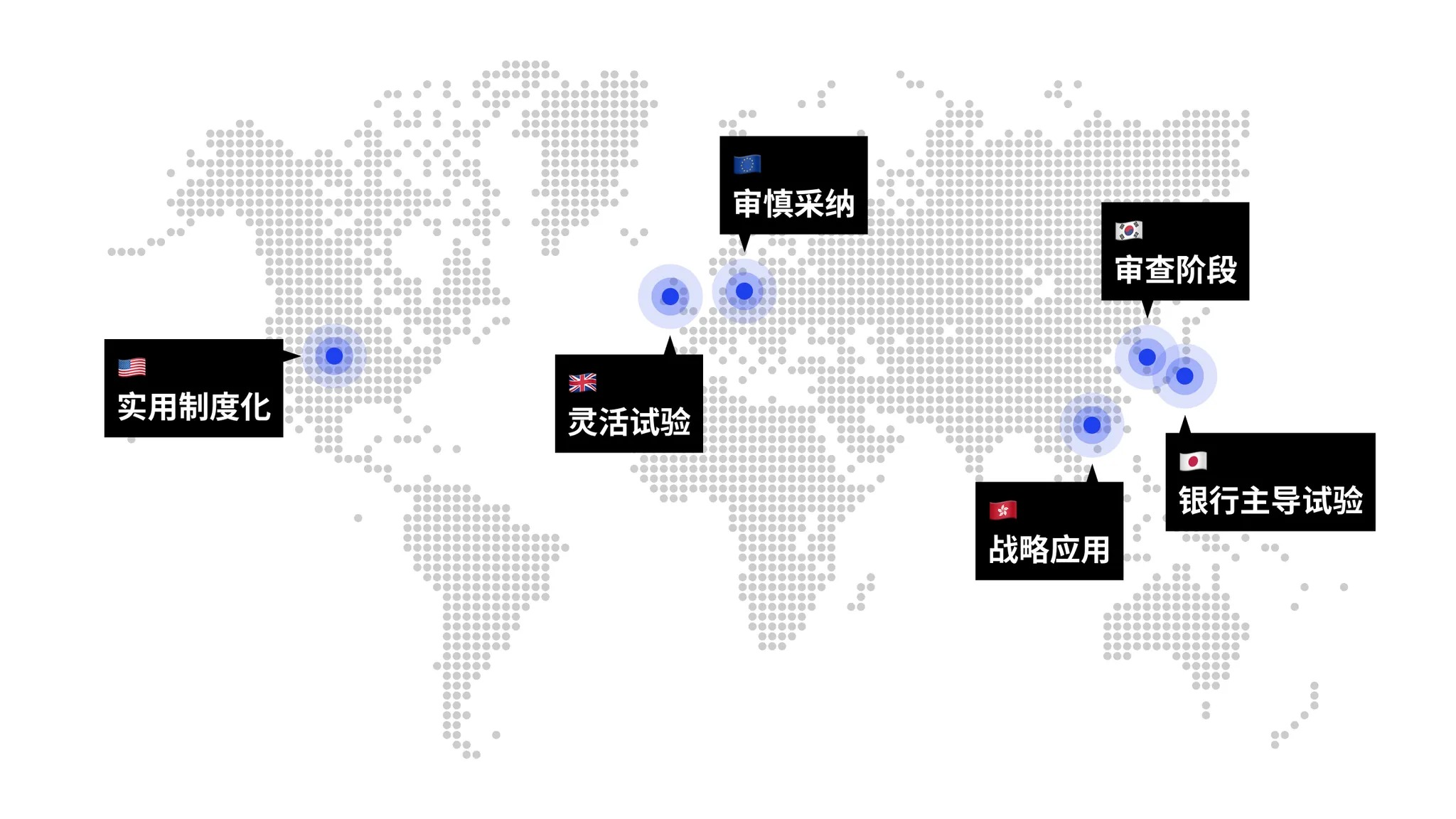

Countries' policies on cash-equivalent collateralized stablecoins vary due to their domestic monetary system structures, the depth of capital markets, the complexity of interest rate transmission mechanisms, and their regulatory philosophies regarding digital assets. In particular, the approaches of the U.S., Europe, Japan, and South Korea to the institutionalization of stablecoins and conflicts with monetary policy differ.

Figure 4: Comparison of Stablecoin Policies in Major Countries

United States: With a deep capital market and a multi-layered interest rate transmission structure composed of the Federal Reserve System, money market funds, and deposit institutions, it is generally believed that government bond-backed stablecoins will not immediately threaten monetary policy. Circle's USDC, BlackRock's sBUIDL, and Ondo's government bond fund-based tokens demonstrate liquidity operating structures that connect digital assets with money market funds, viewed as means of asset securitization and financial innovation. The recently proposed Genius Act represents a legislative trend to formalize private stablecoins under conditions such as high credit collateral requirements and issuer registration requirements.

Europe: The European Central Bank (ECB) maintains a more conservative and restrictive attitude toward private stablecoins. MiCA strictly requires institutional capital, redemption rights, and transparency in collateral operations, effectively implying that only financial institutions can issue them. The ECB is wary that private stablecoins may become competitive instruments against the digital euro and circumvent monetary policy, preferring to prioritize institutional stability over technological experimentation.

Japan: Due to the ultra-low interest rate environment and a bank-centered credit creation structure, the operational space for monetary policy is limited. Therefore, Japan tends to view private stablecoins as auxiliary tools for digital credit expansion. Discussions on bank issuance models are the most active, and there are considerations to allow stablecoin structures backed by government bonds held at a certain ratio of reserves. There is a preference for permissioned structures based on private chains, focusing on building a regulatory-friendly environment.

South Korea: South Korea, with its interest rate-centered monetary policy and relatively shallow capital market characteristics, is one of the countries with significant concerns about the monetary policy implications of government bond-backed stablecoins. The Bank of Korea has pointed out in multiple reports since 2023 that "in the context of adjusting liquidity through policy interest rates, the inflow of digital currencies may undermine the credibility of monetary policy." Governor Lee Chang-yong also stated in May 2025 that "privately issued stablecoins may play a role similar to currency, and the issuance by non-bank institutions should be approached with caution." Currently, the Bank is advancing wholesale CBDC experiments while simultaneously promoting payment experiments based on deposit tokens issued by commercial banks.

United Kingdom: The consultation document released in May 2025 indicates that stablecoin collateral assets can not only use short-term government bonds but also allow for some long-term bonds. This grants issuers broader discretion in asset composition, becoming a notable institutional experiment that recognizes market flexibility and private autonomy.

Hong Kong: Based on the peg structure of the Hong Kong dollar to the U.S. dollar, it allows the use of U.S. government bonds and other USD-based assets as collateral for stablecoins. This is not merely a financial experiment but connects with the policy objective of expanding the national foreign exchange structure strategy. It can be seen as reflecting the central authority's intention to extend the HKD-USD peg structure into digital liquidity through stablecoins.

The stablecoin policies of various countries are not only about risk management or maintaining the effectiveness of monetary policy but are also closely related to the characteristics of the country's capital market, foreign exchange strategy, and macroeconomic goals as a global financial center. The cases of the UK and Hong Kong demonstrate the importance of this strategic approach. This suggests that Korean policymakers should not view stablecoins merely as "objects of control" but should examine how to utilize them as "strategic tools" for deepening capital markets, enhancing international settlement efficiency, and ultimately strengthening the long-term growth drivers of the Korean economy, such as national foreign exchange strategy. This requires moving beyond a purely risk-averse perspective to seize opportunities.

3.3. Bank-Dominated Stablecoin Cultivation

3.3.1. Institutional Role and Importance of Deposit-Based Stablecoins

Deposit-based stablecoins (deposit tokens) issued by banks are viewed as one of the most credible digital liquidity structures by policymakers. This model issues stablecoins based on existing deposit balances, achieving digital circulation without increasing the money supply or distorting interest rate policy, thus enjoying a high level of acceptance within the institutional framework.

However, deposit-based stablecoins are not without risks. Factors such as bank liquidity risk, capital adequacy issues, and the expansion of usage scenarios outside the scope of deposit insurance protection are all considerations in institutional design. Particularly, when large-scale on-chain circulation occurs, it may affect the bank's liquidity structure or the operation of payment networks, necessitating a parallel risk-based approach.

Nevertheless, the policy maintains a relatively friendly stance toward deposit-based stablecoins for the following reasons:

They are associated with the depositor protection system, which is beneficial for consumer protection.

They can be managed within the control of the reserve requirement system and interest rate policy.

They are easier to comply with AML/CFT and foreign exchange regulations under the commercial banking regulatory framework.

Some viewpoints suggest that non-bank stablecoins backed by government bonds can promote innovation in the fintech ecosystem. However, this can largely be achieved through deposit-based structures as well. For example, if global fintech companies require a won stablecoin, it is entirely feasible for domestic banks in South Korea to issue it based on deposits and provide it in the form of APIs. In this case, the API provision can include various functions beyond simple remittance, such as stablecoin issuance, redemption, transaction record inquiries, user KYC status confirmation, and custody status confirmation. Fintech companies can integrate stablecoins as a means of payment and transfer into their services through these APIs or build an automatic clearing system linked to user wallets.

This approach operates within the banking regulatory framework, satisfying depositor protection and AML/CFT requirements while enabling fintech companies to design user experiences that allow for flexible innovation. Particularly, when banks act as issuers, they can adjust circulation under a risk-based approach and, if necessary, connect on-chain payment APIs to internal clearing networks, pursuing both stability and scalability.

From this perspective, the deposit-based stablecoin model can respond to private innovation demands without affecting the right to issue currency or monetary policy, and can be evaluated as a realistic alternative seeking a balance between institutional stability and technological scalability.

Regarding non-bank stablecoins based on public chains, the policy remains cautious. Especially in South Korea, where financial infrastructure is highly developed and the proportion of unbanked populations is low, it can be argued that relying solely on public chain technology is insufficient to prove innovation and necessity.

JPMorgan and MIT DCI (2025) point out that existing stablecoins and ERC standards still have technical limitations that cannot fully meet the actual payment requirements of banks. Therefore, the report proposes a new token standard and smart contract design principles that include regulatory-friendly features, which have become important reference standards for South Korea in reviewing whether to introduce public chain-based payment tokens. Thus, it is more beneficial to first empirically establish bank stablecoins that match technical and institutional requirements, and then discuss the phased possibilities of expansion on public chains while observing global standard-setting trends, balancing the pursuit of policy stability and market innovation.

Moreover, it is no longer appropriate to base discussions on traditional fully closed private chains like Corda, Hyperledger, or Quorum. After all, there are now technologies that can customize both closure and openness, achieve interoperability between private environments, and connect with public chains as needed and for specific purposes. In other words, a hybrid infrastructure based on flexible design is not a one-way closed system but lays the foundation for the coexistence of institutional systems and private innovation.

In this context, to sustain empirical policy discussions on public chain-based stablecoins, it is necessary to combine specific business projects, circulation payment roadmaps, and technical implementation plans to preemptively prove that public chain stablecoins can indeed ensure both liquidity creation and innovative use. Otherwise, situations like the limited liquidity pool of JPYC on Uniswap may recur, isolating it and reducing the likelihood of acceptance within the institutional framework.

Ultimately, the persuasiveness of the policy lies not in a simple "because it must be on a public chain," but in what substantive needs the structure meets and what industrial application possibilities and spillover effects it demonstrates.

3.3.2. Priority Areas for Blockchain Introduction

If deposit-based stablecoins issued by banks become the core pillar of digital liquidity within the system, then the financial infrastructure areas where these stablecoins should be prioritized for introduction become clear. This should not merely be about digitizing payment methods but should focus on addressing structural issues such as trust coordination among multiple institutions, cross-border asset transfers, and ensuring interoperability between systems. Particularly for domestic inter-institutional transaction and payment infrastructures that are already highly developed through centralized systems, the necessity and utility of introducing blockchain may be limited. Conversely, in the context of cross-border asset and payment flows, or in complex structures requiring inter-institutional interoperability, blockchain can serve as a powerful efficiency tool.

Payment Network Clearing: Deposit-based stablecoins can enhance the efficiency of international fund transfers and clearing infrastructure. This includes improvements in foreign exchange transaction clearing (e.g., Project Jura), automation of trade payments through electronic letters of credit and electronic invoices (e.g., smart contracts in Project Guardian), and supplementing the international payment network clearing functions of RTGS systems (e.g., Project Agorá). In trade payments, as shown in cases like Contour and TradeLens, ensuring participant and platform unity is also crucial beyond just technology.

Securities Clearing and Asset Management: They can play a core role in enhancing the efficiency of capital market securities holding and clearing structures. Transforming domestic securities settlement into T+0 and delivery versus payment (DvP) structures (e.g., DTCC's Project Ion and Smart NAV), achieving on-chain asset management structures that combine RWA and deposit tokens (e.g., JPMorgan Kinexys), maximizing liquidity and operational efficiency.

Other Potential Application Areas: Blockchain can structurally address the limitations of existing systems in high-value-added areas, such as designing on-chain securitization structures utilizing repetitive cash flows or enhancing the efficiency of cross-border securities investment clearing. These areas provide clear advantages in legal contract transparency, clearing certainty, speed, and efficiency through blockchain.

These areas are where existing systems have clear limitations in terms of cost, time, and risk management, and they are also high-value-added areas that can be structurally resolved through blockchain. Most importantly, if the same structures used by overseas financial institutions are utilized, the possibility of South Korea's digital finance directly connecting to the global network will also increase.

Furthermore, if the permissioned blockchain structure adopted by South Korea develops into an internationally interoperable technical standard, it can expand to direct connections with overseas financial institutions, foreign exchange swaps, trade settlements, joint issuance and circulation of securities, etc. Cross-border financial interoperability will transcend mere technical choices and become a digital strategic asset for the national economy.

3.3.3. Requirements for Applicable Technical Infrastructure

As the applicable areas for bank-issued deposit-based stablecoins become clearer, the technical infrastructure requirements supporting their implementation also need to be further specified. The core lies in how to meet the necessary conditions of regulatory friendliness, transaction privacy, system control, and high-performance processing while also achieving on-chain automation and global interoperability, which are advantages of blockchain.

The most promising solution is to build a customizable permissioned blockchain system, where each system can be tailored to the needs of the user and can achieve native interoperability between sub-chains. This allows for connections with external chains to be realized as needed while satisfying AML/KYC, regulatory-level privacy protection, and high-performance clearing processing.

A typical case is the Avalanche Subnet architecture. This structure combines the controllability of private chains with cross-chain interoperability capabilities, with the following main features:

Access control and regulatory compliance: Network participants are limited to pre-approved institutions or partners, and all transactions can only be executed after passing KYC/AML verification.

Data privacy protection: User real-name information is not stored on-chain, using a regulatory-compliant pseudonymous model that can be traced under regulatory requirements.

Optional external connectivity: If needed, interoperability with public chains or other subnets can be achieved.

SMBC is planning to issue a yen stablecoin based on the Avalanche Subnet, creating a closed system accessible only to authorized partners. As this major Japanese bank begins to use stablecoin transactions based on Subnet, if South Korea also issues stablecoins using the same architecture in the future, it is expected to create an experimental environment for real-time verification of wholesale stablecoin interoperability between JPY and KRW.

JPMorgan's Kinexys issues deposit-based stablecoins on its proprietary permissioned chain (based on Quorum), automating specific financial operations such as FX trading, repurchase agreements, and securities clearing. Although Kinexys has long operated on the Quorum foundation, it has recently begun testing the privacy-enhancing features of Avalanche Subnet through Project EPIC, particularly attempting to modularly integrate it into specific application scenarios such as portfolio tokenization. However, Kinexys's overall infrastructure has not yet migrated, and it is introducing Avalanche technology in an "integrated module" manner within the existing architecture.

Intain operates its structured finance platform IntainMARKETS based on Avalanche Subnet, supporting the entire process of issuance, investment, and settlement of ABS with on-chain automation, currently managing assets exceeding $6 billion. The platform operates on a permissioned network that complies with AML/KYC and GDPR requirements, enabling multi-party participation structures and effectively reducing the issuance costs and time for small-scale ABS, becoming a representative case of successful blockchain technology implementation in structured finance.

In summary, bank-issued stablecoins are not only payment tools but can also develop into core infrastructure for compliant financial digitization. The connection to public chains should not be an immediate goal but should be promoted as a medium- to long-term direction after regulatory coordination. Currently, a more realistic path is to build infrastructure compatible with the existing institutional financial system in areas such as wholesale payments, securities clearing, and international liquidity management.

3.4. Korean Response Strategy

South Korea's policy environment in the digital currency transformation has not prioritized speed but rather institutional acceptance and policy control. Particularly, the three policy pillars of monetary sovereignty, foreign exchange regulation, and financial stability require a gradual acceptance strategy centered on central banks and commercial banks, rather than a diffusion led by the private sector. Therefore, the Korean response strategy follows three directions:

Institutionally-Centered Stablecoin Cultivation: Build a permissioned infrastructure centered on deposit-based stablecoins issued by banks, prioritizing the application of permissioned structures as seen in global cases, with restrictive introductions of Web3 partnerships through APIs or white-labeling, seeking a balance between stability and innovation.

Regulatory Sandbox for Limited Flexibility Operations: After detailed analysis of the impacts on monetary policy effectiveness, capital flows, and financial stability, allow non-bank entities to experiment within a limited scope only under the regulatory sandbox system, with the clear aim of ensuring institutional responsiveness to technological changes.

Global Linkage and Establishment of Technical Standards: Referencing major national policies such as the Genius Act, EU MiCA, and Japan's bank-led model, establish role distinctions and interoperability standards among CBDC, deposit tokens, and private stablecoins, ensuring that South Korea's institutional financial system has contact points with the global Web3 ecosystem, laying the foundation for the long-term implementation of a comprehensive digital payment system.

In conclusion, the permissioned stablecoin model based on banks is the most executable and institutionally accepted digital currency strategy for South Korea, which will become the technological foundation for enhancing the efficiency of cross-border financial transactions, ensuring inter-institutional interoperability, and circulating digital assets under institutional control. Conversely, non-bank issuance structures should be limited to experiments outside the system, with the basic direction being to maintain a dual structure of digital currency centered on central banks and commercial banks.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。