Original Title: "Stablecoins: Growth Potential and Impact on Banking"

Original Authors: Gordon Y. Liao and John Caramichael

Original Translation: Rhythm BlockBeats

On June 5, stablecoin giant Circle will officially list on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol CRCL, marking the most anticipated IPO in the cryptocurrency space since Coinbase (ticker COIN) went public on Nasdaq in 2021.

According to Bloomberg, Circle plans to issue 24 million shares in this IPO, raising $624 million, with a target valuation of $6.7 billion. However, based on the latest market data, this target has been revised upward to $7.2 billion, and the offering has been oversubscribed by more than 25 times, indicating that the market previously underestimated the enthusiasm for the stablecoin concept.

This enthusiasm is not solely from retail investors; many institutional investors, such as Cathie Wood from Ark Invest and Larry Fink from BlackRock, have publicly stated their intention to make significant purchases, collectively accounting for about 30% of this financing. Just one or two weeks before the official IPO date was confirmed, Circle was also involved in "acquisition rumors" with Coinbase and Ripple.

Related Reading: "While Sprinting for IPO, What Does Circle Want to Do?"

In recent years, stablecoins have emerged as one of the few concepts that institutions can bet on for the growth of the cryptocurrency market and the adoption of blockchain technology, making Circle the first public company in the stablecoin space.

At the end of last month, the Hong Kong Legislative Council passed the "Stablecoin Regulation Bill" in its third reading, leading to a surge in several stablecoin concept stocks and digital currency sectors in both the Hong Kong and A-share markets, with many companies hitting the 20% daily limit. Additionally, according to Caixin, Everbright Holdings saw its stock price soar by 26.6% on June 3 due to its strategic investment in Circle in partnership with IDG Capital in 2016.

Amid the hype, the traditional finance sector has seen a rapid rise in discussions about "What are stablecoins?" In fact, the technology behind stablecoins, especially CBDCs (Central Bank Digital Currencies), has long been a strategic plan for many governments. In the U.S., thanks to the Trump administration's executive ban on CBDCs, the development of "private stablecoins" has advanced rapidly, with the "GENIUS" stablecoin bill passing on May 20.

The U.S. government has conducted extensive research on stablecoin technology itself. On January 31, 2022, the Federal Reserve released a report titled "Stablecoins: Growth Potential and Impact on the Banking System," in which it focused on the potential impact of stablecoins on the banking system and credit intermediation. For readers unfamiliar with stablecoin concepts and knowledge, it may serve as a good "Stablecoins 101" textbook.

Below is the translated content of the Federal Reserve's report "Stablecoins: Growth Potential and Impact on the Banking System":

TL;DR

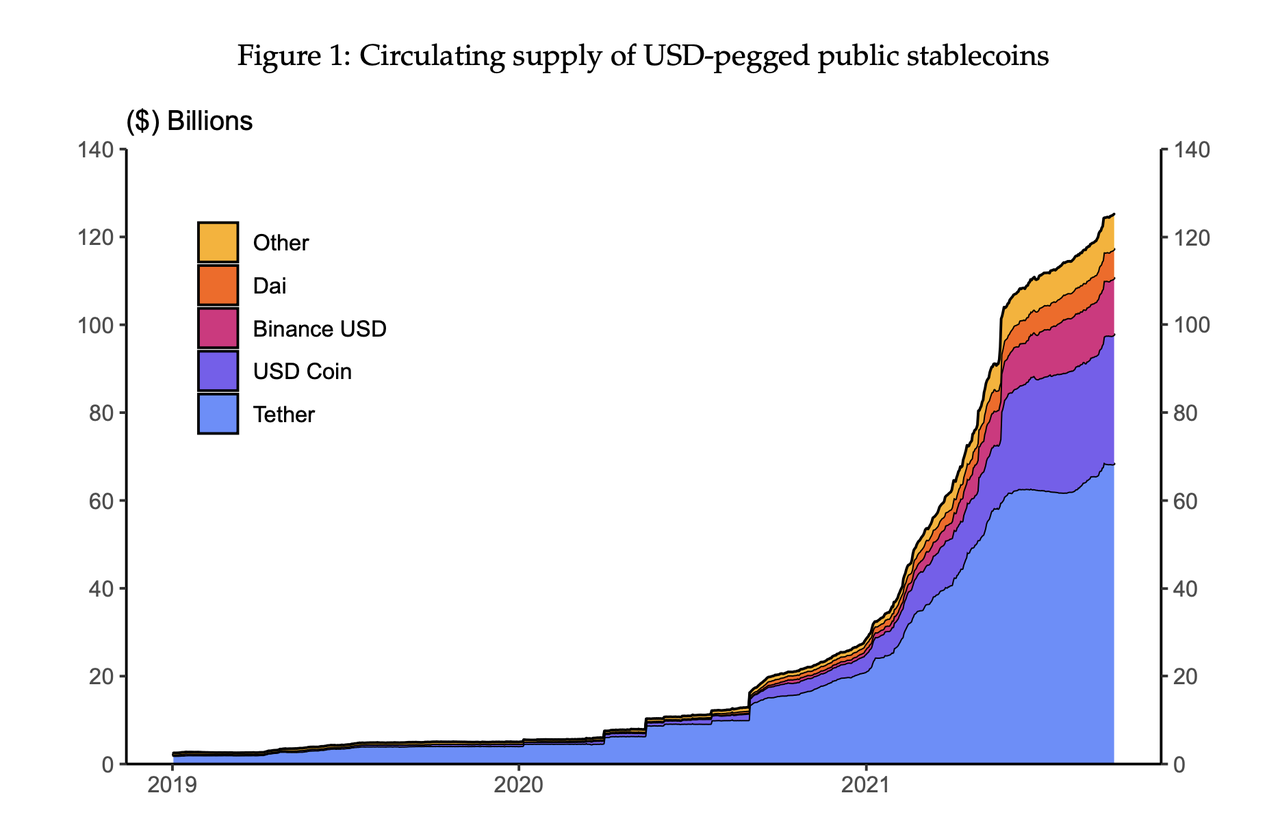

Stablecoins are digital currencies that peg their value to an external reference, typically the U.S. dollar (USD). Stablecoins play a critical role in the digital market, and their growth could stimulate innovation in the broader economy. Over the past year, the circulation of dollar-pegged stablecoins on public blockchains has exploded, reaching nearly $130 billion by September 2021, a more than 500% increase from a year earlier.

As stablecoins gain more attention, a series of questions have arisen, including the stability of their peg, consumer protection, KYC and compliance, as well as the scalability and efficiency of settlements. We will focus on the potential impact of stablecoins on the banking system and credit intermediation. While a range of issues related to stablecoins can be addressed through appropriate institutional safeguards, regulations, and technological advancements, the continued growth of stablecoins in circulation will ultimately impact the traditional banking system in significant ways.

In this document, we first discuss the basics of stablecoins, their current use cases, and their growth potential. Next, we examine the historical behavior of stablecoins during past crises in the cryptocurrency and broader financial markets. We find that dollar-pegged stablecoins exhibit safe asset qualities, as their prices in secondary markets temporarily rise above the peg price during extreme market distress, incentivizing further issuance of stablecoins. We also highlight the "run" risk associated with certain stablecoins backed by non-cash equivalent risk assets.

Finally, we outline potential scenarios for bank reserves, credit intermediation, and central bank balance sheets if stablecoins gain broader attention. Our research suggests that the widespread adoption of asset-backed stablecoins could be supported within a two-tiered fractional reserve banking system without negatively impacting credit intermediation. In such a framework, stablecoin reserves are held as deposits by commercial banks, which engage in fractional reserve lending and maturity transformation similar to traditional bank deposits. We also find that replacing physical cash (banknotes) with stablecoins could lead to more credit intermediation. In contrast, a "narrow" banking framework that requires stablecoin issuers to back their stablecoins with central bank reserves minimizes the risk of stablecoin "runs" but may reduce credit intermediation.

Basics of Stablecoins

Stablecoins are digital currencies recorded on distributed ledger technology (DLT), typically blockchain, that are pegged to a reference value. Most circulating stablecoins are pegged to the U.S. dollar, but stablecoins can also be pegged to other fiat currencies, baskets of currencies, other cryptocurrencies, or commodities like gold. As a store of value and medium of exchange on DLT, stablecoins enable exchanges or integrations with other digital assets.

Stablecoins differ from traditional digital currency records, such as bank deposit accounts, in two main ways. First, stablecoins are cryptographically protected. This allows users to settle transactions almost instantly without double spending or intermediaries facilitating the settlement. On public blockchains, this also allows for transactions 24/7, 365 days a year. Second, stablecoins are typically built on programmable DLT standards, allowing for service composability. In this context, "composability" means that stablecoins can serve as independent building blocks that interoperate with smart contracts (self-executing programmable contracts) to create payment and other financial services. These two key features underpin the current use cases of stablecoins and support innovation in both financial and non-financial sectors.

Since 2020, the usage of stablecoins on public blockchains such as Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, or Polygon has surged. By September 2021, the circulating supply of the largest dollar-pegged public stablecoins approached $130 billion. The chart shows that the circulating supply of public stablecoins grew particularly strong at the beginning of 2021, with an average month-over-month growth of about 30% in the first five months of the year.

Current Types of Stablecoins

Stablecoins are an emerging and broadly defined technology that can take various forms. The technology is currently implemented in specific forms, which we will describe below and summarize in Table 1. However, it is important to note that stablecoin technology is in its infancy and has high innovation potential. The current implementations of stablecoins discussed below, as well as their current status in the regulatory environment, do not reflect all potential deployments of stablecoin technology.

Circulating supply of the top ten public stablecoins pegged to the U.S. dollar by market capitalization. Data from January 2019 to September 2021. Other categories include Fei, TerraUSD, TrueUSD, Paxos Dollar, Neutrino USD, and HUSD.

Public Reserve-Backed Stablecoins

Most existing stablecoins circulate on public blockchains, such as Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, or Polygon. Among these public stablecoins, most are backed by cash-equivalent reserves such as bank deposits, treasury bills, and commercial paper. These reserve-backed stablecoins are also known as custodial stablecoins, as they are issued by intermediaries that act as custodians of cash-equivalent assets and provide 1:1 redemption of stablecoin liabilities in U.S. dollars or other fiat currencies.

The sufficiency and robustness of some public reserve-backed stablecoins have been questioned. In particular, the largest circulating stablecoin, Tether, agreed to pay $41 million to settle a dispute with the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which accused Tether of misrepresenting the sufficiency of its dollar reserves. Other widely used reserve-backed public stablecoins with varying levels of financial audits include USD Coin, Binance USD, TrueUSD, and Paxos Dollar.

Public Algorithmic Stablecoins

Some stablecoins use alternative mechanisms to stabilize their prices rather than relying on the robustness of underlying reserves. These stablecoins are typically referred to as algorithmic stablecoins. While reserve-backed stablecoins are issued as liabilities on the balance sheets of legally registered companies, algorithmic stablecoins are maintained by smart contract systems that operate on public blockchains. The ability to control these smart contracts is typically granted through governance tokens, which are specialized tokens used to vote on changes to the protocol or governance parameters. These governance tokens can also serve as direct or indirect claims on future cash flows from using the stablecoin protocol.

The field of public algorithmic stablecoins is highly innovative and difficult to categorize. However, these stablecoins are generally designed based on two mechanisms: (1) collateral mechanisms and (2) algorithmic peg mechanisms. When users deposit unstable cryptocurrencies (such as Ethereum) into the Dai smart contract protocol, a collateralized public stablecoin, such as Dai, is minted. Users then receive a loan of Dai (pegged to the U.S. dollar) with a collateralization ratio exceeding 100%. If the value of the Ethereum deposit falls below a certain threshold, the loan is automatically liquidated.

In contrast, algorithmic peg mechanisms use automated smart contracts to protect the peg by buying and selling stablecoins along with associated governance tokens. However, these pegs may encounter instability or design flaws, leading to "de-pegging," as exemplified by the algorithmic stablecoin Fei, which briefly lost its peg after launching in April 2021.

Institutional or Private Stablecoins

In addition to reserve-backed stablecoins circulating on public blockchains, traditional financial institutions have also developed reserve-backed stablecoins, also known as "tokenized deposits." These institutional stablecoins are implemented on permissioned (private) DLT and are used by financial institutions and their clients for efficient wholesale transactions. The most notable institutional stablecoin is JPM Coin. JPMorgan and its clients can use JPM Coin for intraday repurchase settlements and manage internal liquidity.

These private, reserve-backed stablecoins are functionally and economically comparable to products offered by certain money transmitters. For example, PayPal and Venmo (a subsidiary of PayPal) allow users to make near-instant transfers and payments within their networks, and the balances held by these companies are similar to reserve-backed stablecoins. The key difference lies in the use of centralized databases rather than permissioned DLT.

Use Cases and Growth Potential of Stablecoins

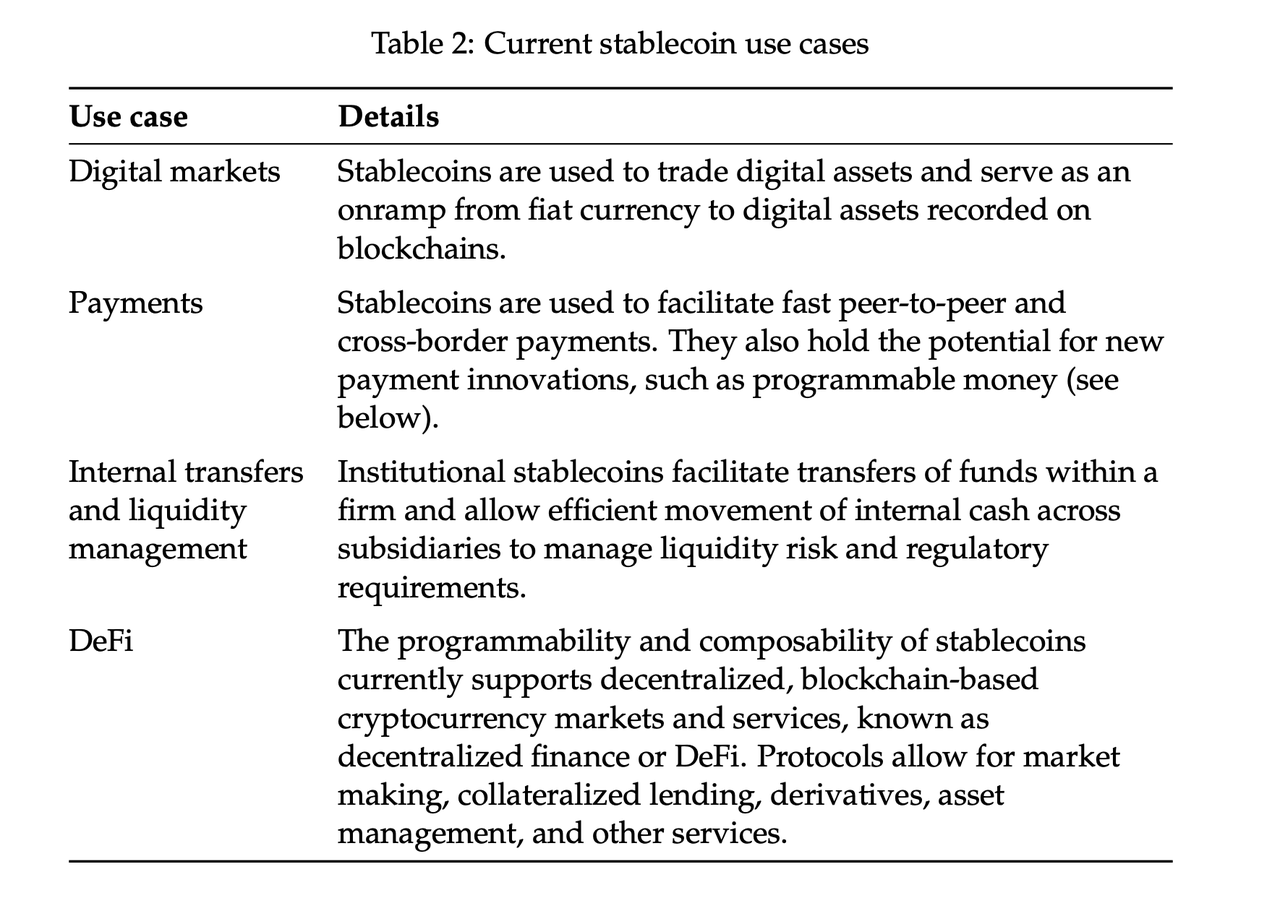

Powerful use cases are driving the growth of various forms of stablecoins currently. We summarize these use cases. The most important current use case for stablecoins is their role in cryptocurrency trading on public blockchains. Investors typically prefer to use public stablecoins for trading cryptocurrencies because this allows for near-instantaneous 24/7/365 trading without relying on non-DLT payment systems or custodial holdings of fiat currency balances.

In addition to being used for crypto trading, both public and institutional stablecoins are currently used for near-instantaneous 24/7 non-intermediated payments, often at low costs. This is particularly relevant for cross-border transfers, which can take days and incur high fees. Companies also use institutional stablecoins to transfer cash almost instantly between their subsidiaries to manage internal liquidity and facilitate wholesale transactions in existing financial markets, such as intraday repurchase agreements. Finally, because public stablecoins are programmable and composable, they are widely used in decentralized, public blockchain-based markets and services known as decentralized finance or DeFi. DeFi protocol systems allow users to directly engage with various cryptocurrency-related markets and services, such as market making, lending, derivatives, and asset management, using stablecoins without traditional intermediaries. As of September 2021, approximately $60 billion in digital assets were collateralized (locked) in DeFi protocols.

Future Growth Potential

The defining characteristics of stablecoins, along with their cryptographic security and programmability, support the strong use cases currently driving the use of existing public and institutional stablecoins. However, these features have the potential to drive innovation beyond the current use cases, which are primarily limited to the cryptocurrency market, certain peer-to-peer payments, and institutional liquidity management by large banks. Looking ahead, stablecoin technology may see diverse implementations and drive innovation in several growth areas: more inclusive payment and financial systems, tokenized financial markets, and microtransactions that facilitate technological advancements like Web 3.

More Inclusive Payment and Financial Systems

Stablecoins have the potential to stimulate growth and innovation in payment systems, enabling faster and cheaper payments. Because stablecoins can be used for near-instantaneous peer-to-peer transfers between digital wallets at potentially low fees, they may lower payment barriers and pressure existing payment systems to provide better services. This is especially important for cross-border transfers, which can take days to settle and incur high fees. These costs and delays are burdensome for low- and middle-income countries.

Stablecoins may also support a more inclusive financial system through the growth of DeFi, which may require stablecoins as a necessary component. It is important to note that DeFi faces significant challenges, including complex user experiences, lack of consumer protection, frequent hacking incidents, protocol malfunctions, and market manipulation. Moreover, almost all DeFi protocols currently only support trading or lending of cryptocurrencies or non-fungible tokens (NFTs). If DeFi protocols mature beyond their current state and integrate with broader financial markets to support real-world economic activities, DeFi could encourage a more inclusive financial system, allowing investors to participate directly in markets without intermediaries. This growth in DeFi could drive increased usage of stablecoins.

Tokenized Financial Markets

Additionally, stablecoins may play a key role in the tokenization of financial markets. This would require converting securities into digital tokens on DLT and using stablecoins for trading and services. For delivery versus payment (DvP) transactions, such as securities purchases, tokenized markets would allow for real-time settlement at very low costs. This could enhance liquidity, trading speed, and transparency while reducing counterparty risk, trading costs, and other market participation barriers. By allowing fractional ownership of tokenized assets and more transparent price discovery, this could be particularly beneficial for certain asset classes, such as real estate. For payment versus payment (PvP) transactions, such as cross-currency swaps, tokenization would also allow for near-instant execution, as opposed to the current traditional T+2 framework, where payments for swaps settle days after the exchange of business. Furthermore, for both types of transactions, tokenized financial markets would benefit from the programmability of DLT, which can automate security services and regulatory requirements, such as required holding periods. If financial markets are partially or fully tokenized, this could drive further growth in the use of stablecoins.

Next-Generation Innovation

Finally, stablecoins have the potential to support next-generation innovations. One example of this innovation is Web 3, which may shift from centralized network platforms and data centers to decentralized networks. In this paradigm, the revenue of internet services and social media platforms would shift from advertising to microtransactions, thanks to the emergence of efficient, integrated online payment systems. For instance, one could envision a search engine or video streaming platform supported by near-instant small payments made with stablecoins, rather than relying on advertising revenue and the sale of user data. If this shift in web services is realized, it could drive further growth in stablecoins.

In summary, the current use of stablecoins is primarily driven by cryptocurrency trading, limited peer-to-peer payments, and DeFi. Looking ahead, stablecoins may achieve further growth by facilitating more inclusive payment and financial systems, the tokenization of financial markets, and potential next-generation innovations like Web 3.

Peg Stability

The stability of stablecoins in relation to their reference value is a core issue. This is not the focus of our paper, but we briefly discuss this important issue here. In this section, we will first outline the sources of peg instability currently associated with public reserve-backed stablecoins and discuss how to address these sources. Then, we will review how stablecoins can act as potential safe assets in digital markets and provide evidence that current public reserve-backed stablecoins may have played this role in the cryptocurrency market.

Currently, the peg instability of public reserve-backed stablecoins takes two forms: redemption risk from investors of the issuer and price dislocation in the secondary market. The former is related to the safety and robustness of the stablecoin reserves. If stablecoin holders lose confidence in the robustness of the stablecoin, panic may ensue. A run on stablecoins poses a risk of spillover to other asset classes as stablecoin reserves are sold off or unloaded to meet redemption demands. Additionally, a run on stablecoins may disrupt markets and services that rely on stablecoins through interoperability, causing further distress. We believe that this type of instability can be addressed through appropriate institutional and/or regulatory safeguards, such as transparent financial audits and sufficient requirements for the liquidity and quality of stablecoin reserves. Recent discussions in Quarles (2021) have highlighted concerns surrounding redemption risk and the extent to which they can be addressed.

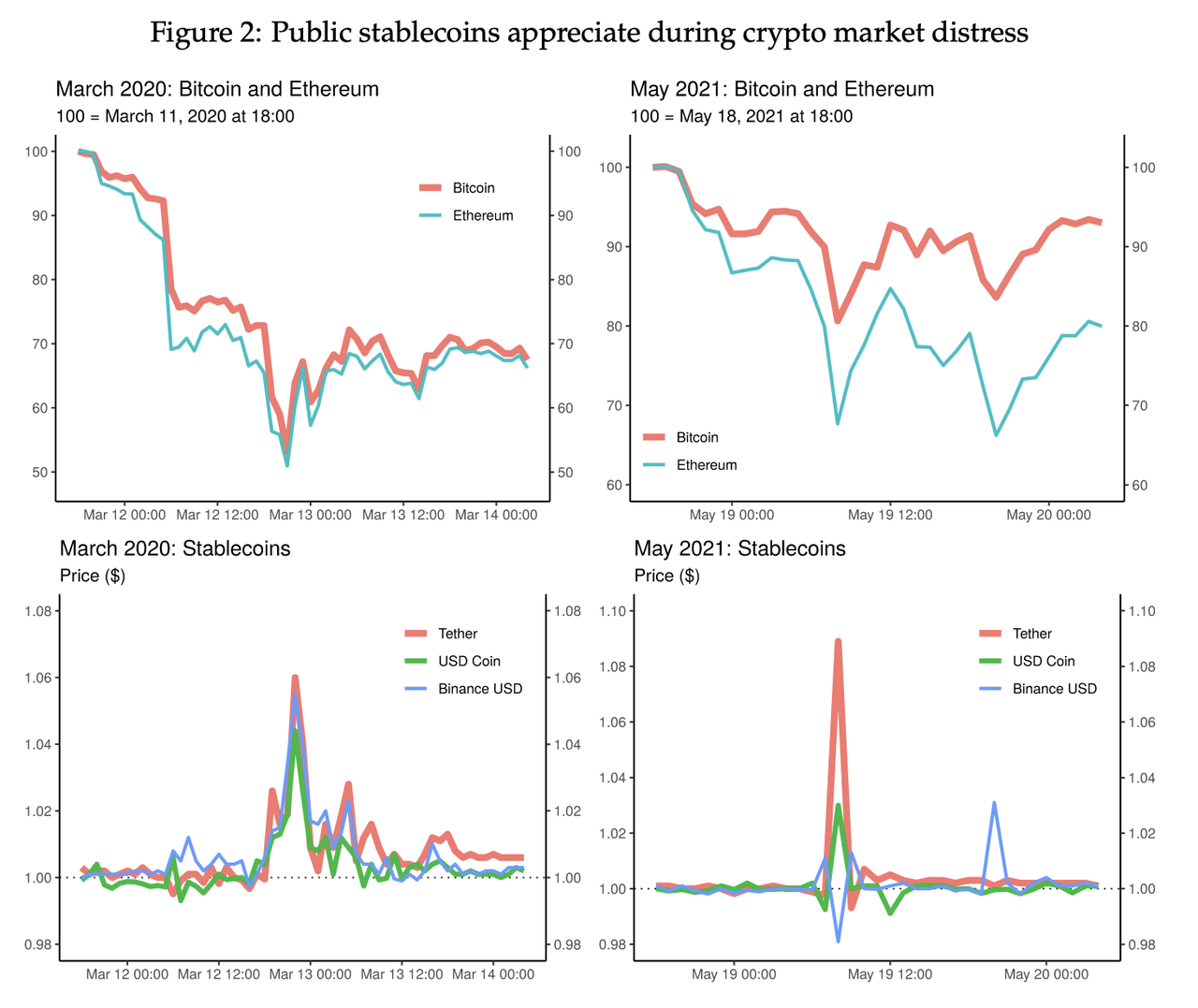

The second form of peg instability for public reserve-backed stablecoins arises from supply and demand imbalances in the secondary market. Since these stablecoins trade on both centralized and decentralized trading platforms, they are susceptible to demand shocks that may temporarily dislocate their peg until the stablecoin issuer adjusts supply. In particular, as public stablecoins serve as a store of value in public blockchain-based markets, these stablecoins experience high demand during cryptocurrency market distress, as investors rush to liquidate their speculative positions into stablecoins. During these events, the prices of major public reserve-backed stablecoins often temporarily appreciate until the issuer adjusts supply. For example, the chart shows the cryptocurrency market crashes on March 12, 2020, and May 19, 2021. The first event occurred during a period of widespread market turmoil surrounding concerns about the spread of Covid-19. The second event occurred during a downturn in the cryptocurrency market associated with significant deleveraging. During both periods, as the prices of speculative cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum plummeted by 30% to 50%, the prices of major public reserve-backed stablecoins surged significantly.

In these extreme cryptocurrency market distress events, stablecoins appreciated as a digital safe asset, while more speculative crypto assets were in free fall until stablecoin issuers could increase their supply and purchase reserves and/or stablecoins experienced downward price pressure from arbitrageurs. The behavior of these public stablecoins is unique, unlike high-quality money market funds, which experienced significant outflows during the most severe periods of the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic.

These events demonstrate the potential of stablecoins to serve as digital safe havens during market distress. While discussions about the financial stability risks of public reserve-backed stablecoins primarily focus on the redemption risks unique to individual stablecoin reserve forms, our analysis suggests that counter-cyclical demand for stablecoins in the secondary market can reduce redemption risks during broader market downturns. With appropriate safeguards and regulations, stablecoins have the potential to provide stability comparable to traditional forms of safe value.

Potential Impact of Stablecoins on Credit Intermediation

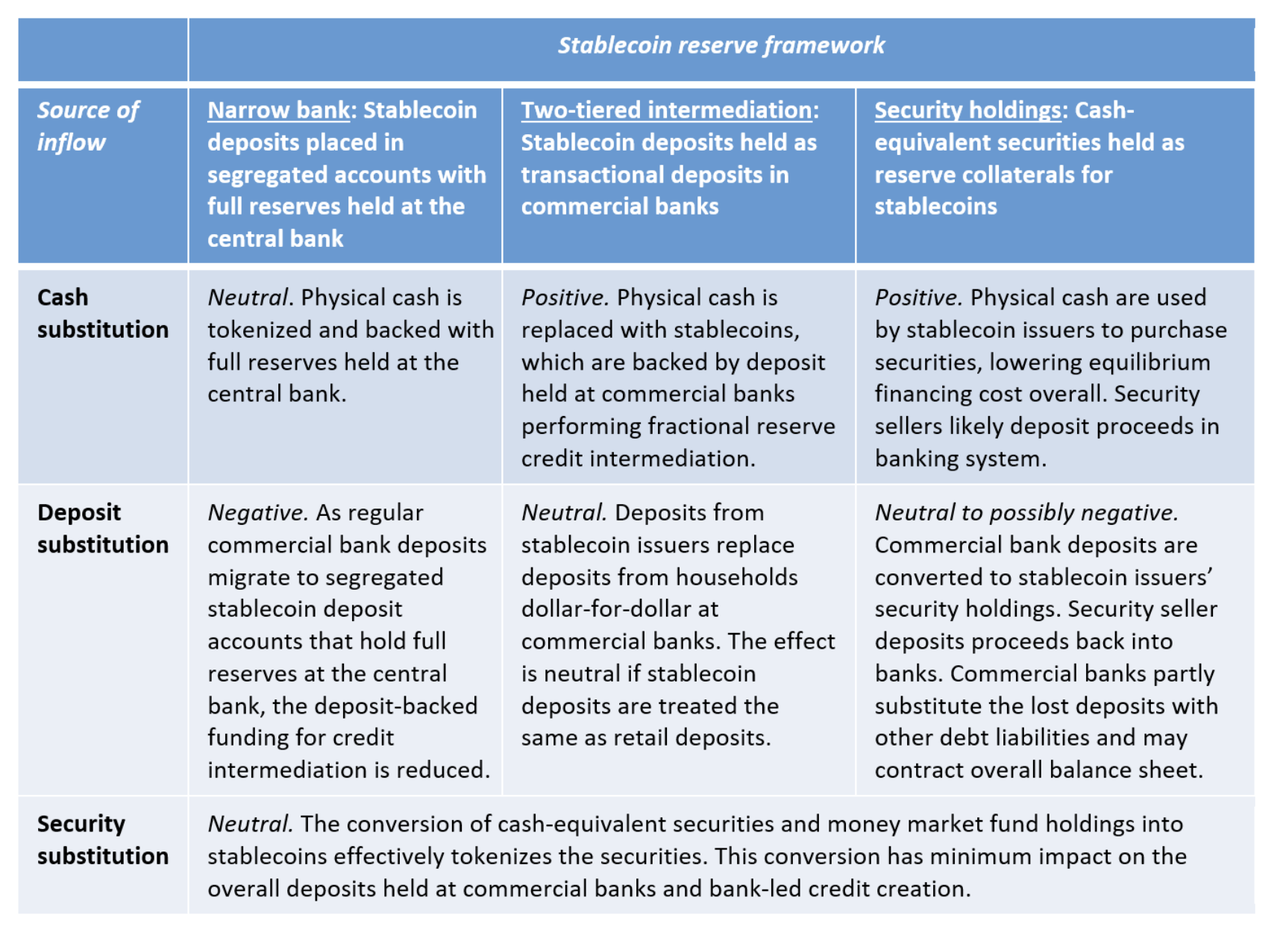

If stablecoins are widely adopted throughout the financial system, they could have significant impacts on the balance sheets of financial institutions. Regulators, market participants, and scholars are particularly concerned about the potential for stablecoins to disrupt bank-led credit intermediation. In this section, we analyze several possible scenarios for the widespread adoption of reserve-backed stablecoins in the financial system. We focus on reserve-backed stablecoins rather than algorithmic stablecoins, as reserve-backed stablecoins are currently the largest and most closely linked to the existing banking system. Using these scenarios, we emphasize how the impact of stablecoin adoption on credit provision critically depends on two factors: the sources of inflows into stablecoins and the composition of stablecoin reserves.

We summarize our findings. We find that in most of the scenarios we consider, credit provision may not be negatively impacted. In fact, replacing physical cash (banknotes) with stablecoins may allow for more bank-led credit supply. One notable exception that could lead to significant credit disintermediation is if stablecoins are fully backed by central bank reserves, which we refer to as a narrow banking framework. In this framework, redemption risk is minimized at the cost of greater credit disintermediation.

Sources of Inflows

If stablecoins are widely adopted, the primary inflows may come from three sources: physical cash (banknotes), commercial bank deposits, and cash-equivalent securities (or money market funds). First, as a form of digital currency, stablecoins will replace a portion of the circulating banknotes, especially as the economy becomes more digital. In some of our scenarios, as users substitute physical cash with reserve-backed stablecoins, we see an increase in credit supply. This is because banknotes are direct liabilities of the central bank, which are replaced by reserve-backed stablecoins, depending on the reserve framework, which can create credit through loans or securities purchases.

Secondly, if households and businesses prefer to hold stablecoins instead of traditional balances at commercial banks, stablecoins may see inflows from commercial bank deposits. Policymakers are very interested in this source of inflow, as there are widespread concerns that a large amount of alternative deposits could disrupt the credit supply of commercial banks. We show that the impact of deposit substitution on credit supply can be positive, negative, or neutral, depending on the reserve framework. Finally, stablecoins may also see inflows from cash-equivalent securities (or money market funds). This may have no impact on credit supply, as it requires funds to be cycled back into the banking system, which we will discuss in later sections.

Reserve Composition

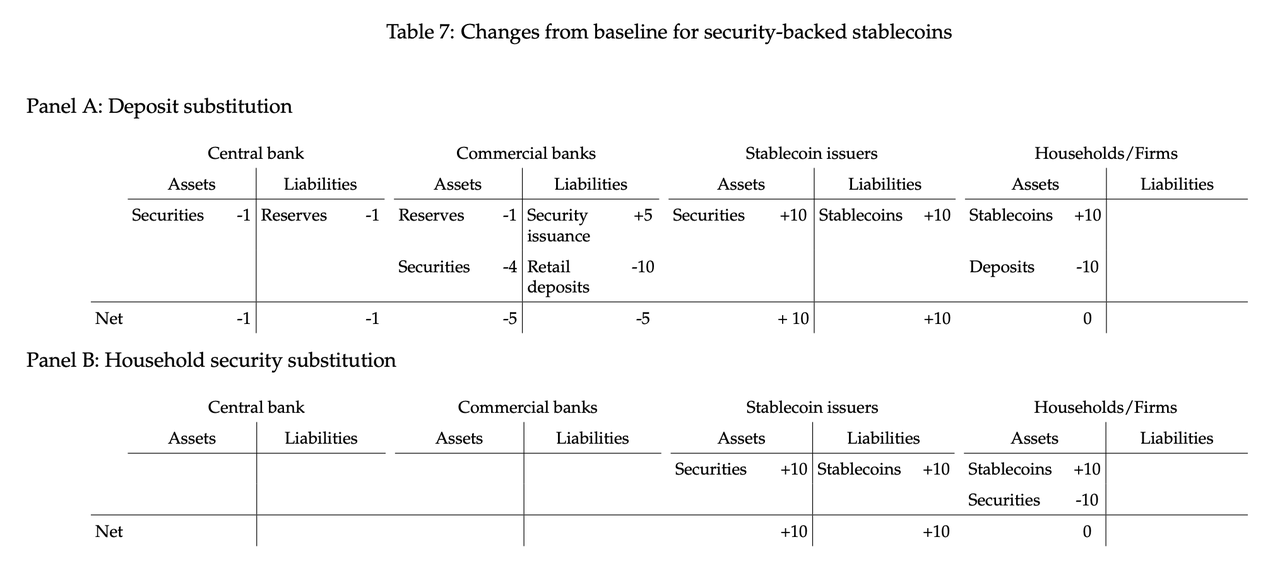

The impact of widely adopted reserve-backed stablecoins on credit provision also depends on the composition of stablecoin reserves. We propose three reasonable stablecoin reserve frameworks: narrow banking, two-tier intermediation, and securities holdings, as illustrated above.

In a narrow banking framework, stablecoins need to be backed by commercial bank deposits, which are fully supported by central bank reserves. Equivalently, commercial banks could potentially issue fully backed stablecoins (or tokenized deposits) backed by central bank reserves. The narrow banking approach is roughly equivalent to a retail central bank digital currency (CBDC), where the digital currency is a liability of the central bank, but households and companies can use it through intermediaries such as commercial banks or fintech companies. The People's Bank of China has adopted this framework in its state-supported digital currency (known as Digital Currency Electronic Payment), the digital yuan, or e-CNY. The proposed STABLE Act in the U.S. also mentions the possibility of requiring stablecoins to maintain reserves at the central bank.

While the narrow banking framework can ensure the peg stability of stablecoins, as it effectively acts as a conduit for central bank digital currency, this reserve framework poses the greatest risk of credit disintermediation. Financial stress or panic could lead to a significant transfer of conventional commercial bank deposits into narrow banking stablecoins, which could disrupt credit supply. Although this credit disruption effect can be mitigated by limiting stablecoin holdings and differential reserve interest rates, the overall structure of banks' narrow approach to stablecoin reserves could undermine the stability of the banking system. Additionally, the narrow banking approach could lead to an expansion of the central bank's balance sheet to accommodate the reserve balance demands of stablecoin issuers.

Concerns about narrow banking stablecoins reflect broader concerns about narrow banking, which the Federal Reserve has already noted. In a recently proposed regulation that would affect narrow banks (officially referred to as pass-through investment entities or PTIEs), the Federal Reserve stated, "We are concerned that [narrow banks] could disrupt financial intermediation in unpredictable ways and could also pose negative implications for financial stability" (Regulation D: Reserve Requirements of Depository Institutions, 2019). Furthermore, the Federal Reserve outlined serious concerns about the demand for reserve balances, stating, "[Narrow banks] could have very large demands for reserve balances. To maintain an appropriate monetary policy stance, the Federal Reserve may need to meet this demand by expanding its balance sheet and reserve supply."

In contrast to the narrow banking framework, under the two-tier intermediation framework, stablecoins would be backed by commercial bank deposits used for partial reserve banking. Similarly, commercial banks could also issue stablecoins or provide tokenized deposits for partial reserve banking. It is important to clarify that this does not mean that stablecoins are not adequately backed. On the contrary, stablecoin issuers rely on commercial bank deposits as assets, and commercial banks engage in partial reserve banking with stablecoins and/or stablecoin deposits, meaning that stablecoins are ultimately supported by a combination of loans, assets, and central bank reserves. This would effectively re-label some conventional deposits as stablecoin deposits. Importantly, to keep bank intermediation unchanged, the treatment of stablecoin deposits must be the same as that of non-stablecoin deposits in terms of statutory reserve ratios, liquidity coverage ratios, and other regulatory and self-imposed risk limits.

Finally, stablecoin issuers could hold cash-equivalent securities, such as treasury bills and high-quality commercial paper, instead of depositing funds in commercial banks. These securities can be purchased directly or indirectly through money market funds. This is the primary framework adopted by current issuers of public reserve-backed stablecoins, such as Tether, which Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell recently noted, "is like a money market fund."

Scenario Building

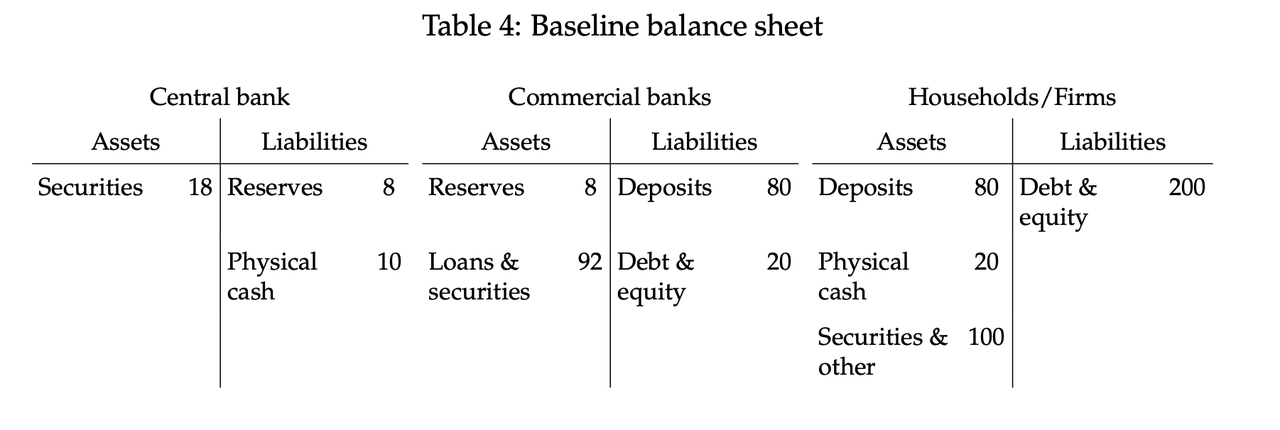

In our scenarios, we will consider the impact of one or more fiat reserve-backed stablecoins being widely adopted in a stylized version of the banking system. The baseline balance sheet of the banking system is shown in the figure. Specifically, we consider the case where households and businesses replace $10 of cash, commercial bank deposits, or securities, and then we perform accounting work to determine how the adoption of stablecoins would affect the balance sheets of the central bank, commercial banks, and households and businesses. We analyze how this impact varies based on the reserve framework of the stablecoins and their sources of inflow.

It is important to note that we made several key assumptions when constructing these scenarios. First, we do not know the specific form of the stablecoins being adopted. Our scenarios are not intended to analyze, for example, the specific impact of the widespread adoption of existing stablecoins like Tether. We do not distinguish whether the adopted stablecoins are institutional tokenized deposits, stablecoins circulating on public blockchains, or other forms. Second, we only present illustrative advantage cases. In reality, stablecoins can see inflows from various sources and hold various assets as reserves. Third, these scenarios do not capture secondary spillover effects or feedback loops, nor do they address heterogeneous impacts within the industry. Finally, we assume a 10% statutory reserve ratio for traditional deposits at commercial banks.

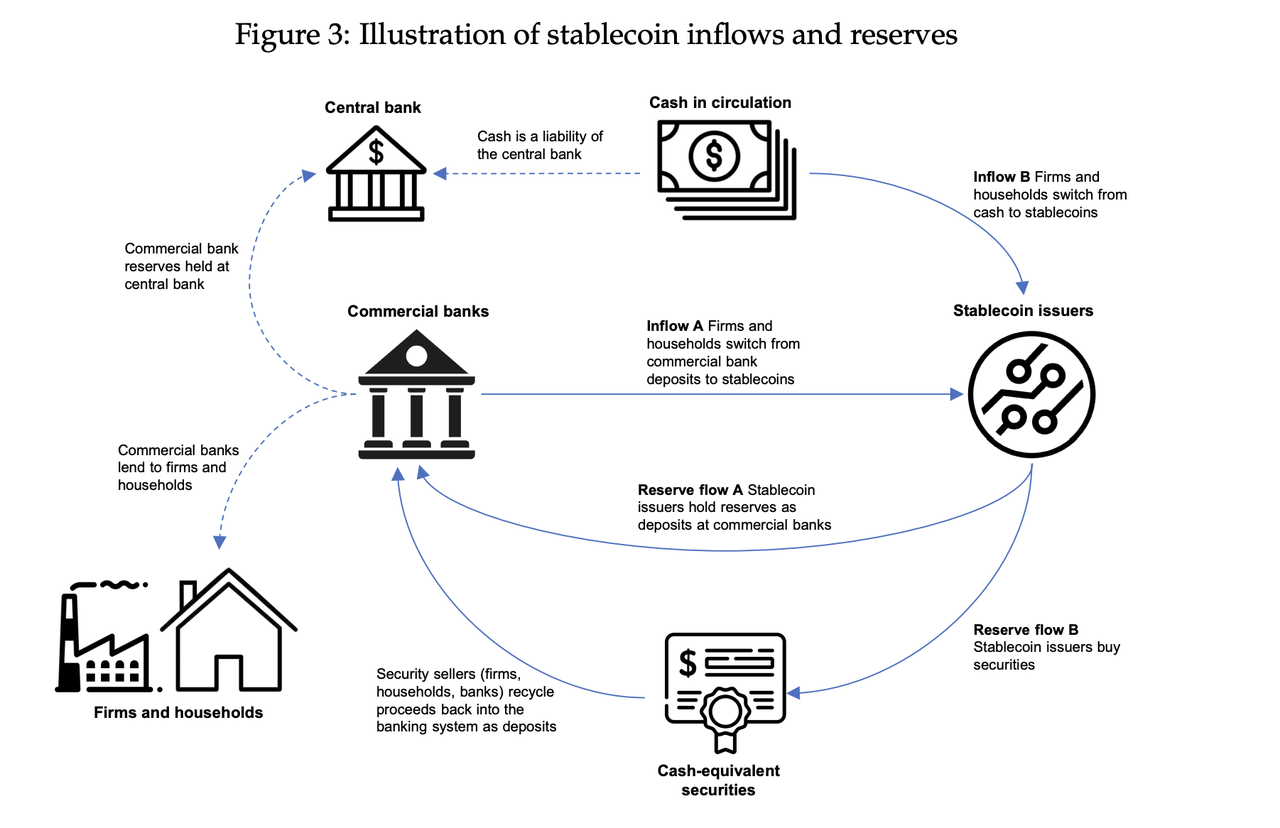

To illustrate the complex flows between the various parts of the banking system that support our marginal case scenarios, we visualize a subset of the stablecoin inflows and reserve allocations we have discussed in the figure. Specifically, we use charts to show the inflow of commercial bank deposits (Inflow A) and cash (Inflow B) into stablecoins, as well as how these funds are allocated to reserves in the form of commercial bank deposits (Reserve Flow A) and securities (Reserve Flow B).

In the figure, we see how stablecoin inflows and reserve flows are interconnected. Companies and households substitute stablecoins for deposits (Inflow A) and cash (Inflow B). Stablecoin issuers deposit some of these funds into the commercial banking system, holding reserves as commercial bank deposits (Reserve Flow A) and using these funds to purchase securities as reserves (Reserve Flow B). These securities purchases will also cycle funds back into the banking system, as the sellers of the securities ultimately receive the proceeds from the sale and deposit them back into the banking system. As shown, these flows affect the central bank, which maintains cash and central bank reserves as liabilities, as well as companies and households that obtain loans from commercial banks. While this figure does not capture all flows between these entities, it symbolizes how the widespread adoption of stablecoins could reshape the complex financial relationships within the banking system.

Scenario Analysis

Narrow Banking Framework:

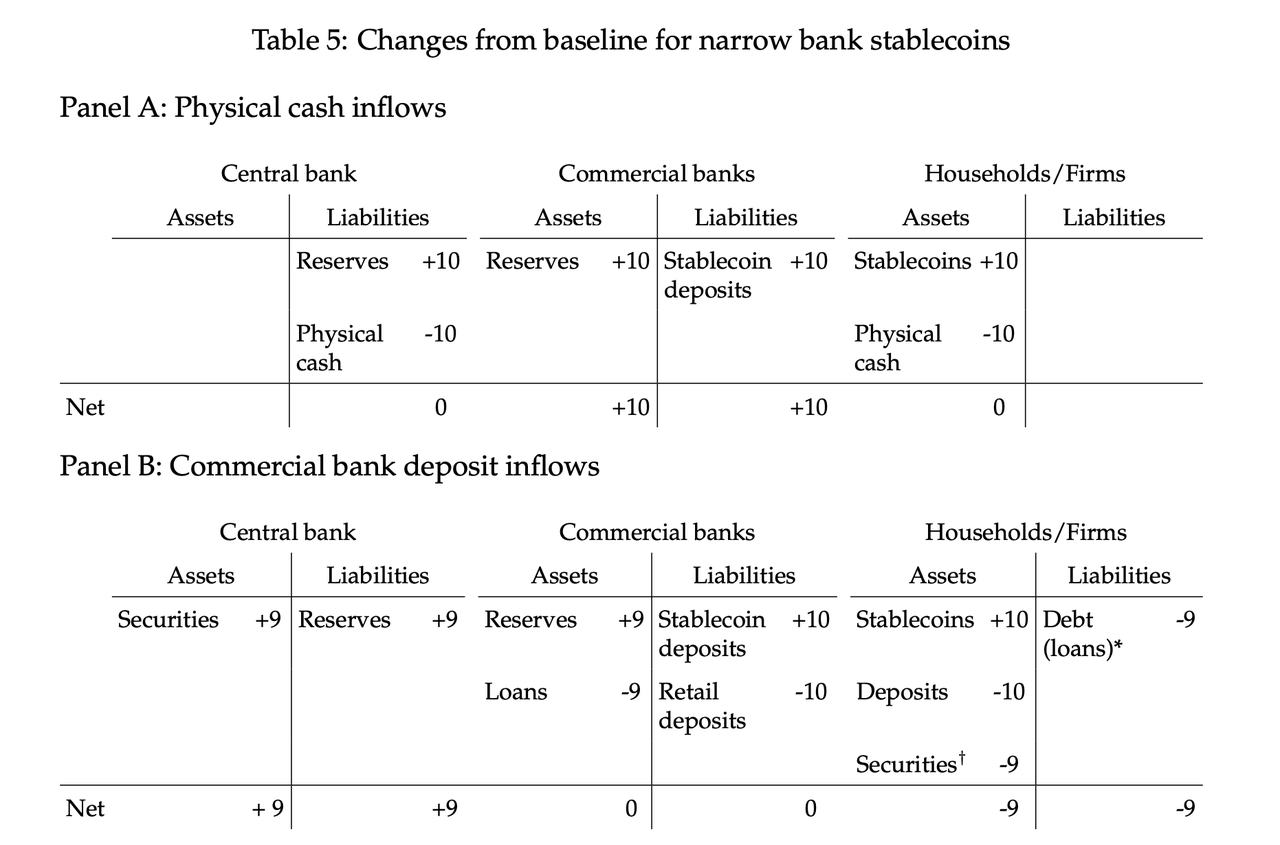

As mentioned earlier, the narrow banking framework poses the greatest risk to credit provision, depending on the source of inflows. In our narrow banking scenario, as shown in the table, we find that inflows of physical cash into narrow banking stablecoins will have a neutral impact on credit supply, while commercial bank deposits will disrupt credit supply.

In Panel A (cash inflow scenario), we see that stablecoins replace cash on the balance sheets of households and companies. The inflow of cash leads to an indirect increase in the balance sheets of commercial banks and their reserves. The central bank's balance sheet is restructured, with reserve liabilities replacing cash liabilities. The net effect is an expansion of the commercial bank's balance sheet, but no change in credit provision. This situation assumes that banks are not constrained by the size of their balance sheets. That is, narrow bank deposits and associated reserve holdings are exempt from leverage calculations. This exemption from leverage calculations for central bank reserve holdings has been adopted by regulators in different jurisdictions.

Panel B shows the narrow banking scenario of deposit migration to stablecoins. Since stablecoin deposits remain fully on the balance sheets of commercial banks, banks must reduce their asset holdings to accommodate the decline in non-stablecoin deposit funds. The central bank's balance sheet will then expand to accommodate the increased demand for reserve balances without offsetting the decline in cash liabilities. In this case, we assume that the central bank will meet the increased reserve demand by purchasing securities. This assumption of central bank easing is based on previous determinations made by the Federal Reserve regarding narrow banks, as mentioned above, in relation to Regulation D: Reserve Requirements of Depository Institutions (2019). However, if the central bank determines the size of its balance sheet, we present two alternatives in Appendix Table A1. In the first alternative, commercial banks significantly shrink their balance sheets to compensate for the shortfall in deposit funds. In the second case, commercial banks compensate for the lost deposit funds by issuing debt securities. The result is a further reduction in bank-led credit creation.

We do not envision a scenario where narrow banking stablecoins see significant inflows from securities holdings. In this case, the impact on credit provision could be neutral. Under the same assumptions as above, the net impact on credit supply should be minimal if the central bank meets the increased reserve demand by purchasing securities (from households). Unlike directly holding securities, the migration to stablecoins would allow households to hold stablecoins backed by central bank reserves, which in turn are supported by securities. This situation also assumes that the increased narrow bank reserves are not affected by leverage ratios, as mentioned above.

Two-Tier Intermediation Framework:

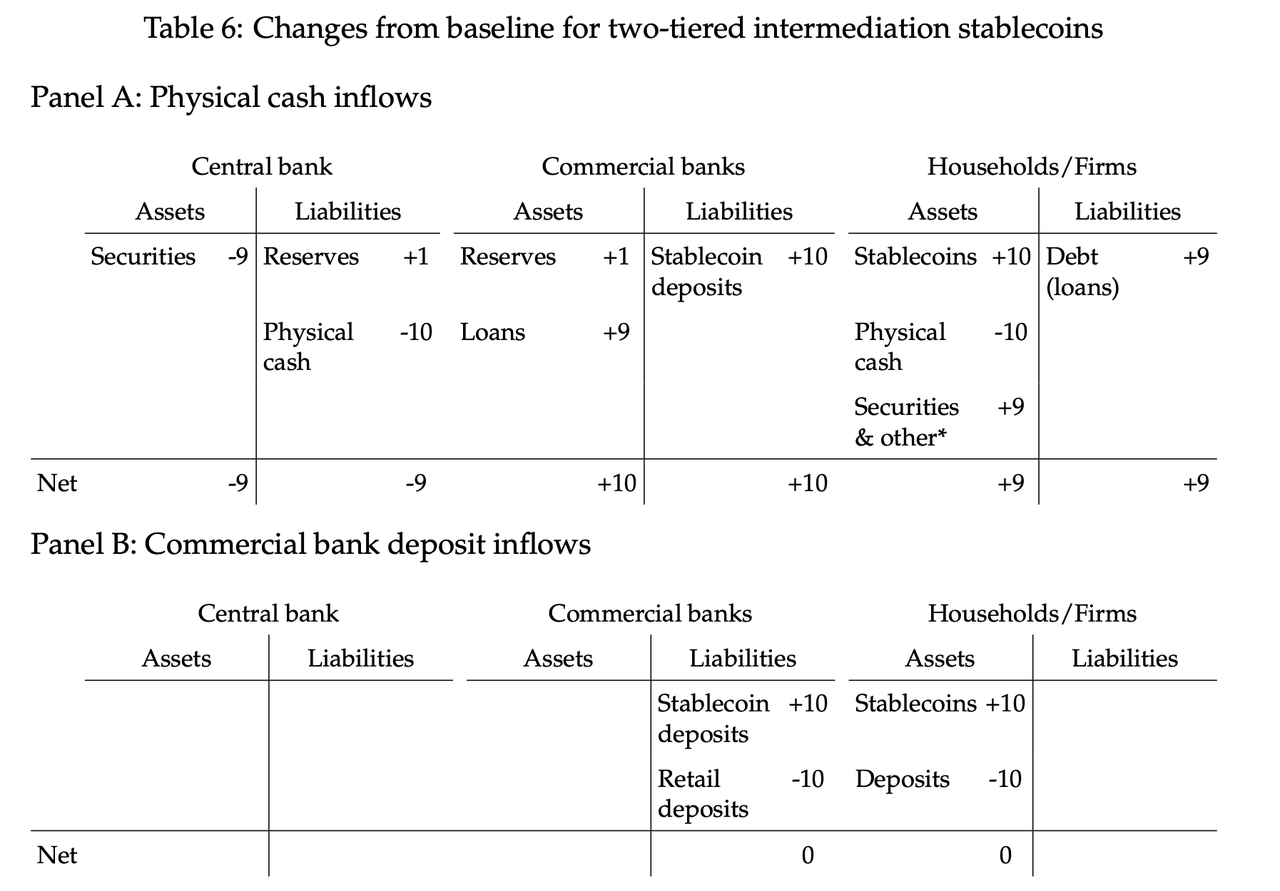

For the two-tier intermediation framework shown in the table below, we find that significant inflows into stablecoins will have a neutral to positive impact on credit supply. Panel A shows the case of exchanging cash for stablecoins. As commercial banks engage in partial reserve banking with stablecoin deposits, their balance sheets expand with the growth of credit and securities holdings, which account for most of the expansion. The central bank experiences a slight contraction in its net balance sheet, with a slight increase in reserves and a significant decrease in cash liabilities. Households accumulate more assets, expanding funding in bank loans. The impact on credit provision is positive. Panel B shows the two-tier intermediation scenario with deposit substitution. The overall balance sheets and asset holdings of commercial banks and the central bank remain unchanged. The only change is in the composition of commercial bank liabilities, as time deposits are converted into stablecoin deposits. As mentioned earlier, this situation assumes that the treatment of stablecoin deposits is the same as that of non-stablecoin deposits in terms of statutory reserve ratios, liquidity coverage ratios, and other regulatory and self-imposed risk limits.

Securities Holding Framework:

As shown in the table below, the impact of widely adopted collateral-backed stablecoins is the most unpredictable. Many scenarios are possible. In Panel A, we present a scenario where securities-backed stablecoins see inflows from commercial bank deposits. We assume that stablecoin issuers procure securities from commercial banks rather than from households and corporate sectors. In this case, as households exchange deposits for stablecoins, commercial banks compensate for the lost deposit funds by issuing their own securities. Additionally, commercial banks may reduce their securities portfolios to offset the loss of deposit funds. If banks primarily adjust the asset side of their balance sheets by changing their securities holdings, the size of the bank loan portfolio may remain unchanged. In this scenario, the central bank's balance sheet also slightly contracts due to the loss of bank reserves.

Panel B illustrates the scenario where households exchange cash-equivalent securities for stablecoins. This would lead to the effective tokenization of cash-like securities without directly affecting the credit supply of the banking system. We also consider another scenario (not shown) where securities-backed stablecoins experience inflows from households and corporate sectors while selling securities to commercial banks. The sellers of the securities are households and corporate sectors, rather than the commercial banks described in Table 7 Panel A. The net impact on credit provision is neutral, as the commercial bank deposit balances held by households and companies purchasing stablecoins are ultimately recycled back into the banking system by transferring them to other households and companies selling securities to stablecoin issuers. This restructuring of securities holdings is illustrated in Figure 3 through Inflow A and Reserve Flow B. The end result is a change in the balance sheet, similar to that in Panel B.

Finally, we did not describe a scenario where collateral-backed stablecoins see inflows from physical cash. However, this could have a neutral or positive impact on credit creation. If stablecoin issuers use cash to purchase existing securities, and this cash is ultimately not deposited into the banking system, it would not affect credit supply, as this would constitute a direct exchange of cash for securities. However, if the cash used to purchase existing securities is deposited into the banking system, or if this cash is used to fund the issuance of new securities, it could increase credit supply by increasing commercial banks' loans and securities purchases, or by lowering the equilibrium cost of issuing securities. In summary, the possible impact is a moderate increase in credit supply.

Summary

As digital assets gain wider adoption and the use cases for programmable digital currencies become clearer, stablecoins have seen significant growth over the past year. This rapid increase has raised concerns about potential negative impacts on banking activities and the traditional financial system. In this report, we discussed the current use cases and potential growth of stablecoins, analyzed historical events of unstable pegs, and illustrated different scenarios of how stablecoins impact the banking system. As mentioned in the introduction, this paper does not consider all potential impacts of stablecoins on financial stability, monetary policy, consumer protection, and other important unexplored issues. We focus on balance sheet effects and credit intermediation under a series of reasonable assumptions.

We studied reserve-backed stablecoins and found that the impact of stablecoin adoption on traditional banks and credit provision may vary depending on the source of inflows and the composition of stablecoin reserves. In various scenarios, a two-tier banking system can support the issuance of stablecoins while maintaining traditional forms of credit creation. In contrast, the narrow banking stablecoin framework can provide the greatest stability but may come with potential costs of credit disintermediation. Finally, if it is believed that dollar-pegged stablecoins have sufficient collateral, they can serve as a safe haven during market distress compared to other crypto assets.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。