撰文:Sleepy.txt

PayPal 要开银行了。

12 月 15 日,这家拥有 4.3 亿活跃用户的全球支付巨头,正式向美国联邦存款保险公司(FDIC)和犹他州金融机构部门递交了申请,计划成立一家名为「PayPal Bank」的工业银行(ILC)。

不过,就在短短三个月前的 9 月 24 日,PayPal 刚刚宣布达成一项重磅交易,将手中高达 70 亿美元的「先买后付」贷款资产打包卖给了资产管理公司 Blue Owl。

当时的电话会上,CFO 杰米·米勒信誓旦旦地向华尔街强调,PayPal 的战略是「保持轻资产负债表」,要释放资本,提高效率。

这两件事很矛盾,一边追求「轻」,却又一边申请银行牌照,要知道,做银行是世界上最「重」的生意之一,你需要缴纳巨额保证金,接受最严苛的监管,还要自己背负存款和贷款的风险。

在这个拧巴的决定背后,一定藏着一个由于某种紧迫原因而不得不做的妥协。这根本不是一次常规的商业扩张,而更像是一场针对监管红线的抢滩登陆。

对于为什么要开银行,PayPal 官方给出的理由是「为了向小企业提供更低成本的贷款资金」,但这个理由根本经不起推敲。

数据显示,自 2013 年以来,PayPal 已经累计向全球 42 万家小企业发放了超过 300 亿美元的贷款。也就是说,在没有银行牌照的这 12 年里,PayPal 照样把贷款业务做得风生水起。既然如此,为什么偏偏要在这个时间点去申请银行牌照呢?

要回答这个问题,我们得先搞清楚:过去这 300 亿美元的贷款,到底是谁放出去的?

发贷款,PayPal 只是个「二房东」

PayPal 的官方新闻稿中的放贷数据很好看,但有一个核心事实通常是被可以模糊处理掉的。这 300 亿美元的每一笔贷款,真正的贷款方都不是 PayPal,而是一家位于犹他州盐湖城的银行——WebBank。

绝大多数人可能从未听说过 WebBank。这家银行极其神秘,它不开设面向消费者的分支机构,不打广告,甚至官网都做得十分简略。但在美国金融科技的隐秘角落里,它却是一个绕不开的庞然大物。

PayPal 的 Working Capital 和 Business Loan、明星公司 Affirm 的分期付款、个人贷款平台 Upgrade,背后的贷款方都是 WebBank。

这就涉及到一个叫「Banking as a Service(BaaS)」的商业模式:PayPal 负责获客、做风控、搞定用户体验,而 WebBank 只负责一件事情——出牌照。

用一个更通俗的比喻,PayPal 在这个生意里,只是一个「二房东」,真正的房产证在 WebBank 手里。

对于 PayPal 这样的科技公司来说,这曾经是一个完美的解决方案。申请银行牌照太难、太慢、太贵,而在美国 50 个州分别申请放贷牌照更是繁琐至极的行政噩梦。租用 WebBank 的牌照,就相当于是一条 VIP 快速通道。

但「租房子」做生意,最大的风险在于房东随时可能不租了,甚至把房子卖掉或者拆掉。

2024 年 4 月,发生了一件让所有美国金融科技公司脊背发凉的黑天鹅事件。一家名为 Synapse 的 BaaS 中介公司突然申请破产,直接导致超过 10 万用户的 2.65 亿美元资金被冻结,甚至有 9600 万美元直接下落不明,有人损失了毕生积蓄。

这场灾难让所有人意识到,「二房东」模式其实存在非常大的漏洞,一旦中间某个环节出纰漏,你辛辛苦苦积累的用户信任会在一夜之间崩塌。于是监管机构开始对 BaaS 模式展开严厉审查,多家银行因 BaaS 合规问题被罚款和限制业务。

对 PayPal 来说,虽然合作的是 WebBank 而不是 Synapse,但风险逻辑是一样的。如果 WebBank 出问题,PayPal 的贷款业务将瘫痪;如果 WebBank 调整合作条款,PayPal 没有议价权;如果监管机构要求 WebBank 收紧合作,PayPal 只能被动接受。这就是「二房东」的困境,自己在费劲地做生意,但命脉还是掌握在别人手里。

除此之外,让管理层下定决心要自己单干的,是另一个更赤裸的诱惑:高息时代的暴利。

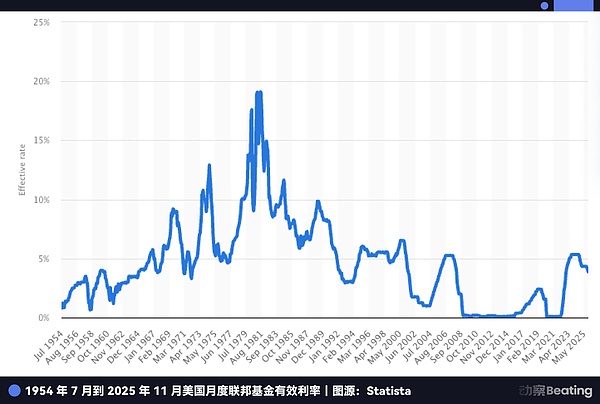

在过去零利率的十年里,做银行并不算是一门性感的生意,因为存贷利差太薄了。但在今天,情况完全不同。

即便美联储已经开始降息,但美国的基准利率依然维持在 4.5% 左右的历史高位。这意味着,存款本身就是一座金矿。

看看 PayPal 现在的尴尬处境:它拥有 4.3 亿活跃用户的庞大资金池,这些钱躺在用户的 PayPal 账户里,然后 PayPal 不得不把这些钱存入合作银行。

合作银行拿着这些低成本的钱,去购买收益率 5% 的美国国债或者发放更高利息的贷款,赚得盆满钵满,而 PayPal 只能分到一点点残羹冷炙。

如果 PayPal 拿到了自己的银行牌照,就能直接把这 4.3 亿用户的闲置资金变成自家的低成本存款,然后左手买国债,右手放贷款,所有的利差收益,全部归自己所有。在这几年的高息窗口期里,这代表着几十亿美元级别的利润差距。

但是,如果只是为了摆脱 WebBank,PayPal 其实早就该动手了,为什么偏偏要等到 2025 年?

这就必须提到 PayPal 内心深处另一个更紧迫、更致命的焦虑:稳定币。

发稳定币,PayPal 还是个「二房东」

如果说贷款业务上的「二房东」身份只是让 PayPal 少赚了钱、多担了心,那么在稳定币战场上,这种依赖关系正在演变成一场真正的生存危机。

2025 年,PayPal 的稳定币 PYUSD 虽然迎来了爆发式增长,市值在三个月内翻了三倍,飙升至 38 亿美元,甚至 YouTube 都在 12 月宣布集成 PYUSD 支付。

但在这些热闹的战报背后,有一个事实,PayPal 同样不会在新闻稿里强调:PYUSD 不是 PayPal 自己发行的,而是通过与纽约的 Paxos 公司合作发行的。

这又是一个熟悉的「贴牌」故事,PayPal 只是品牌授权方,这就好比 Nike 不自己开工厂生产鞋子,而是把 Logo 授权给代工厂。

在过去,这更像是商业分工,PayPal 把产品和流量握在手里,Paxos 负责合规和发行,大家各吃各的饭。

但 2025 年 12 月 12 日,这种分工开始变味。美国货币监理署(OCC)对包括 Paxos 在内的几家机构,给出了国家信托银行(national trust bank)牌照的「有条件批准」。

这虽然不是传统意义上能吸储、能拿 FDIC 保险的「商业银行」,但它意味着 Paxos 正在从代工厂走向有番号、能站到台前的发行方。

再把《GENIUS Act》的框架放进来,你就能理解 PayPal 为什么急。法案允许受监管的银行体系通过子公司发行支付型稳定币,发行权和收益链条会越来越往「有牌照的人」手里集中。

以前 PayPal 还能把稳定币当成一个外包模块,现在外包方一旦具备更强的监管身份,它就不再只是供应商,它也可以成为一个可替代的合作对象,甚至是潜在的对手。

而 PayPal 的尴尬在于,它既不掌握发行底座,也不掌握监管身份。

USDC 的推进、OCC 对信托类牌照的放行,都在提醒它一件事:稳定币这场仗,最后比的不是谁先把稳定币发出来,而是谁能把发行、托管、清算、合规这几根绳子攥在自己手里。

所以,PayPal 与其说是想做银行,不如说是在补一张门票,否则它就只能永远站在场外。

更要命的是,稳定币对 PayPal 的核心业务构成了降维打击。

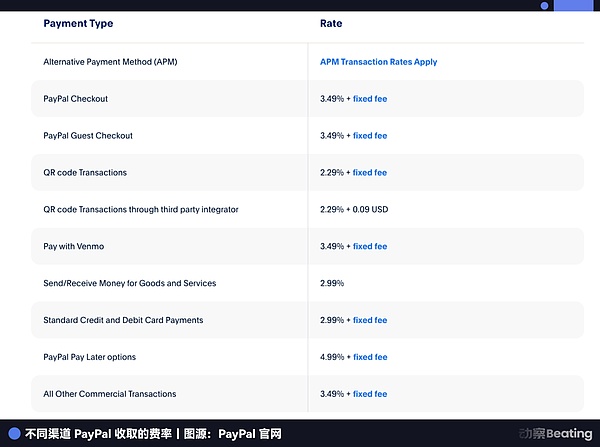

PayPal 最赚钱的生意是电商支付,靠的是每笔交易抽取 2.29~3.49% 的手续费。但稳定币的逻辑完全不同,它几乎不收交易费,赚钱靠的是用户沉淀资金在国债上的利息。

当亚马逊开始接受 USDC,当 Shopify 上线稳定币支付,商家们会面临一个简单的算术题:如果能用接近零成本的稳定币,为什么还要给 PayPal 交 2.5% 的过路费?

目前,电商支付占据了 PayPal 一半以上的业务营收。这两年,它眼看着市场份额从 54.8% 一路下滑到 40%,如果再不掌握稳定币的主动权,PayPal 的护城河将被彻底填平。

PayPal 目前的处境很像当年推出 Apple Pay Later 业务的苹果。2024 年,苹果因为没有银行牌照,处处受制于高盛,最终干脆关停了这项业务,退回到了自己最擅长的硬件领域。苹果可以退,因为金融对它来说只是锦上添花,硬件才是它的核心竞争力。

但 PayPal 退无可退。

它没有手机,没有操作系统,没有硬件生态。金融就是它的全部,是它唯一的粮仓。苹果的退是战略收缩,而 PayPal 如果敢退,等待它的就是死亡。

所以,PayPal 必须向前进。它必须拿到那张银行牌照,把稳定币的发行权、控制权、收益权全部抓回自己手里。

但是,想在美国开银行谈何容易?尤其是对于一家背负着 70 亿美元贷款资产的科技公司来说,监管机构的审批门槛简直高得吓人。

于是,为了拿到这张通往未来的船票,PayPal 精心设计了一场精妙绝伦的资本魔术。

PayPal 的金蝉脱壳

现在,让我们把视线拉回到文章开头提到的那个矛盾。

9 月 24 日,PayPal 宣布把 70 亿美元的「先买后付」贷款打包卖给了 Blue Owl,CFO 高调宣布要「变轻」。当时,华尔街的分析师们大多以为这只是为了修饰财报,让现金流看起来更漂亮。

但如果你把这件事和三个月后的银行牌照申请放在一起看,就会发现这其实不是矛盾,而是一套精心设计的组合拳。

如果不卖这 70 亿应收帐款,PayPal 申请银行牌照的成功率几乎为零。

为什么?因为在美国,申请银行牌照需要完成一次极其严格的「体检」,监管机构(FDIC)手里拿着一把尺子,叫「资本充足率」。

它的逻辑很简单,你的资产负债表上趴着多少高风险资产(比如贷款),你就必须拿出相应比例的保证金来抵御风险。

想象一下,如果 PayPal 背着这 70 亿美元的贷款去敲 FDIC 的大门,监管官一眼就会看到这沉重的包袱:「你背着这么多风险资产,万一坏账了怎么办?你的钱够赔吗?」这不仅意味着 PayPal 需要缴纳天文数字般的保证金,更可能直接导致审批被拒。

所以,PayPal 必须在体检之前,先进行一次全面的瘦身。

这笔卖给 Blue Owl 的交易,在金融行话里叫远期流动协议。这个设计非常精明。PayPal 把未来两年新发放的贷款债权(也就是「已经印出来的钞票」)和违约风险,统统甩给了 Blue Owl;但它极其聪明地保留了承销权和客户关系,也就是把「印钞机」留给了自己。

在用户眼里,他们依然是在向 PayPal 借钱,依然在 PayPal 的 App 里还款,一切体验没有任何变化。但在 FDIC 的体检报告上,PayPal 的资产负债表瞬间变得极其干净、清爽。

PayPal 通过这招金蝉脱壳,完成了身份上的转换,它从一个背负沉重坏账风险的放贷人,变成了一个只赚取无风险服务费的过路人。

这种为了通过监管审批而刻意进行的资产大挪移,在华尔街并非没有先例,但做得如此坚决、规模如此之大,实属罕见。这恰恰证明了 PayPal 管理层的决心,哪怕把现有的肥肉(贷款利息)分给别人吃,也要换取那张更长远的饭票。

而且,这场豪赌的时间窗口正在快速关闭。PayPal 之所以如此急迫,是因为它看中的那个「后门」,正在被监管层关上,甚至是焊死。

即将关闭的后门

PayPal 申请的这张牌照,全称叫「工业银行」(Industrial Loan Company,简称 ILC),如果你不是深资金融从业者,大概率没听说过这个名字。但这却是美国金融监管体系里,最为诡异、也最令人垂涎的一个存在。

看看这张拥有 ILC 牌照的企业名单,会感到一种强烈的违和感:宝马、丰田、哈雷戴维森、塔吉特百货……

你可能会问:这些卖车的、卖杂货的,为什么要开银行?

这就是 ILC 的魔力所在。它是美国法律体系中,唯一一个允许非金融巨头合法开银行的「监管漏洞」。

这个漏洞源于 1987 年通过的《竞争平等银行法》(CEBA)。虽然法律名字叫「平等」,但它却留下了一个极其不平等的特权:它豁免了 ILC 的母公司注册为「银行控股公司」的义务。

如果你申请的是普通银行牌照,母公司必须接受美联储那种从头管到脚的穿透式监管。但如果你持有的是 ILC 牌照,母公司(比如 PayPal)就不受美联储管辖,只需要接受 FDIC 和犹他州层面的监管。

这意味着你既享受了银行吸收存款、接入联邦支付系统的国家级特权,又完美避开了美联储对你商业版图的干涉。

这就是所谓的监管套利,而更诱人的是它允许「混业经营」。这就是宝马和哈雷戴维森的玩法,产业链垂直整合。

宝马银行不需要物理柜台,因为它的业务完美嵌入在买车的流程里。当你决定买一辆宝马时,销售系统会自动对接宝马银行的贷款服务。

对于宝马来说,它既赚了你买车的利润,又吃掉了车贷的利息。哈雷戴维森更是如此,它的银行甚至能给那些被传统银行拒之门外的摩托车手提供贷款,因为只有哈雷自己知道,这些死忠粉的违约率其实很低。

这正是 PayPal 梦寐以求的终极形态:左手支付,右手银行,中间是稳定币,所有环节不让外人插手。

看到这里,你一定想问既然这个漏洞这么好用,为什么沃尔玛、亚马逊不去申请这个牌照,不自己开一家银行呢?

因为传统银行界恨透了这个后门。

银行家们认为,让拥有海量用户数据的商业巨头开银行,简直是降维打击。2005 年,沃尔玛曾申请过 ILC 牌照,结果引发了全美银行业的集体暴动。银行协会疯狂游说国会,理由是如果沃尔玛银行利用超市的数据优势,只给在沃尔玛购物的人提供廉价贷款,那社区银行还怎么活?

在巨大的舆论压力下,沃尔玛于 2007 年被迫撤回申请。这一事件直接导致了监管层对 ILC 的「冷藏」,从 2006 年到 2019 年,整整 13 年,FDIC 没有批准任何一家商业公司的申请。直到 2020 年,Square(现在的 Block)才艰难地打破了僵局。

但现在,这道刚刚重开的后门,又面临着被永久关闭的风险。

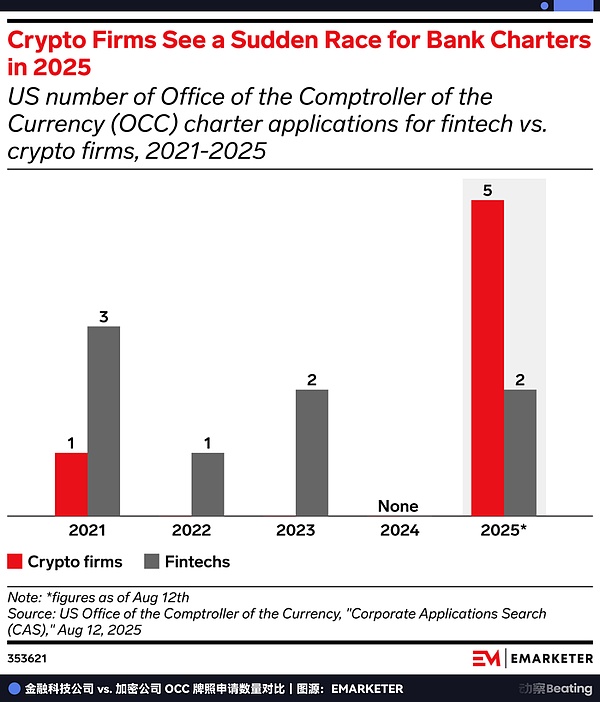

2025 年 7 月,FDIC 突然发布了一份关于 ILC 框架的征求意见稿,这被视为监管收紧的强烈信号。与此同时,国会里相关的立法提案从未停止过。

于是,大家开始一窝蜂地抢起了牌照。2025 年美国银行牌照申请数量达到了 20 份的历史峰值,其中仅 OCC(货币监理署)收到的申请就达 14 份,相当于过去四年的总和。

大家心里都清楚,这是关门前最后的机会。PayPal 这次是在和监管机构赛跑,如果你不在漏洞被法律彻底堵死之前冲进去,这扇门可能就永远关闭了。

生死突围

PayPal 费尽周折争取的牌照,其实是一张「期权」。

它的当前价值是确定的:自主发放贷款,在高息环境下吃利差。但它的未来价值,在于赋予了 PayPal 进入那些目前被禁止、但未来充满想象力的禁区的资格。

看看华尔街最眼红的生意是什么?不是支付,而是资产管理。

在没有银行牌照之前,PayPal 只能做一个简单的过路财神,帮用户搬运资金。但一旦拥有了 ILC 牌照,它就拥有了合法的托管人身份。

这意味着 PayPal 可以名正言顺地替 4.3 亿用户保管比特币、以太坊,甚至未来的 RWA 资产。更进一步,在未来的《GENIUS Act》框架下,银行可能是唯一被允许连接 DeFi 协议的合法入口。

想象一下,未来 PayPal 的 App 里可能会出现一个「高收益理财」按钮,后端连接的是 Aave 或 Compound 这样的链上协议,而中间那道不可逾越的合规屏障,由 PayPal Bank 来打通。这将彻底打破 Web2 支付和 Web3 金融之间的那堵墙。

在这个维度上,PayPal 不再是和 Stripe 卷费率,而是在构建一个加密时代的金融操作系统。它试图完成从处理交易到管理资产的进化。交易是线性的,有天花板,而资产管理是无限游戏。

看懂了这一层,你才能理解为什么 PayPal 要在 2025 年的年末发起这场冲锋。

它非常清楚,自己正被夹在时代的门缝里。身后,是传统支付业务的利润被稳定币归零的恐惧;身前,是 ILC 这个监管后门即将被永久焊死的紧迫。

为了挤进这扇门,它必须在 9 月卖掉 70 亿美元的资产来刮骨疗毒,只为换取那张能决定生死的入场券。

如果把时间拉长到 27 年,你会看到一个充满宿命感的轮回。

1998 年,当 Peter Thiel 和 Elon Musk 创立 PayPal 的前身时,他们的使命是「挑战银行」,用电子货币消灭那些陈旧、低效的金融机构。

27 年后,这个曾经的「屠龙少年」,却拼尽全力想要「成为银行」。

商业世界里,没有童话,只有生存。在加密货币重构金融秩序的前夜,继续做一个游离于体系之外的「前巨头」只有死路一条。唯有拿到那个身份,哪怕是通过「走后门」的方式,才能活到下一个时代。

这是一场必须在窗口关闭前完成的生死突围。

赌赢了,它是 Web3 时代的摩根大通;赌输了,它就只是上一代互联网的遗址。

留给 PayPal 的时间,已经不多了。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。